Ironically, almond hull rot typically affects trees with a heavy crop that have been well tended, ones that have been irrigated and fertilized properly.

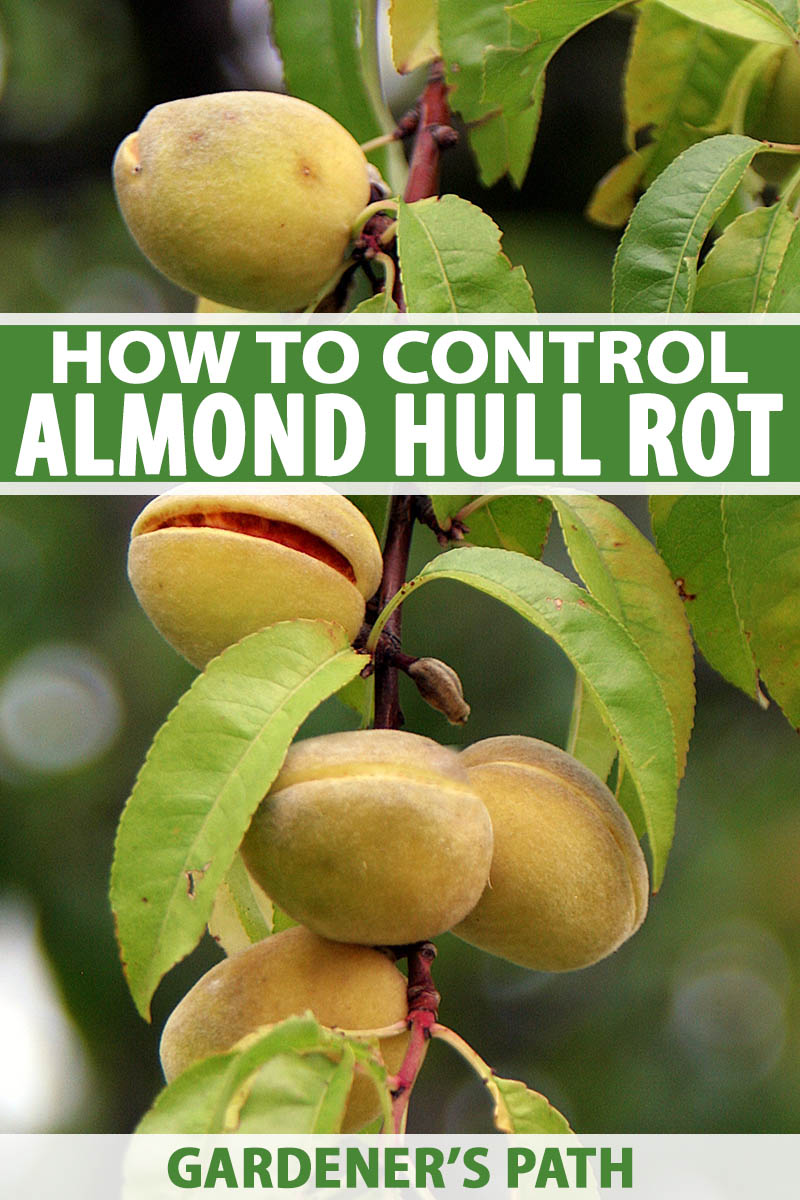

The first symptoms of this disease are the withering and death of some of the shoots.

Rhizopus and Monilinia are the primary types of fungi known to be responsible for this affliction.

However, you can greatly reduce the incidence of this rot by cutting back on your irrigation and fertilization practices.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Read on to learn how to manage this disease.

What You’ll Learn

Initial Symptoms

While examining your lush almond trees several weeks before harvest, you may notice that the leaves on some shoots have withered and died.

This is an indication that you should look at your almonds more closely, because this symptom could indicate that the fruit (drupes) are under attack by the fungi that cause hull rot.

The process of invasion results in the death of the shoot and of the strikes (fruiting wood), and this will reduce the productivity of the tree in the future.

Nuts may also be more difficult to remove from dead shoots during harvest. This makes them prime habitat for the dreaded naval orange worm.

The Fungi That Cause Hull Rot

Almond trees are susceptible to these species of fungi from the beginning of hull split until the hulls dry. The timing on this can range from 10 days to 2 months.

Since the hull is full of nutrients and water, when it splits, this provides the perfect environment for opportunistic fungi, species that take advantage of existing conditions rather than initiating their own invasion.

Scientific experts have studied two types of fungi widely over the years and determined that they are responsible for hull rot. More recently, additional types of fungi have also been implicated in this disorder.

The exact symptoms may vary depending on which fungus is the culprit, but one constant will be a brown area observed outside of the hull.

The Classic Duo

One of the traditional types of fungi involved is Monilinia. You may know this fungus as a source of brown rot on fruit.

Another potential pathogen is one that you are probably intimately familiar with, perhaps you do not realize it. Rhizopus stolonifer has black spores, and can totally destroy a loaf of bread and turn it black in the process.

You can tell which is which on the nuts by thoroughly examining the hull. Monolinia will produce tan growth in the brown area, either inside or outside of the hull.

In contrast, black fungal growth on the inside indicates the presence of Rhizopus.

These fungi produce a toxin known as fumaric acid that is transported from the nuts to the shoots and leaves, causing the death of spurs and leaves.

The Newly Identified Culprits

Recent research has identified two additional types of fungi that are associated with this rot – the common mold Aspergillus, and Phomopsis.

You can identify Aspergillus by its flat black spores found between the shell and hull, in contrast to those of Rhizopus, which look like a multitude of black spores on the inside of the hull.

An Aspergillus infection can stain the kernel and reduce the quality of the nut. The symptoms of Phomopsis vary.

The Most Susceptible Trees

Nonpareil, Sonora, and Kapareil are the commonly planted varieties that are the most susceptible to hull rot.

You can find a table of varieties and their susceptibility in this article from the Sacramento Valley Orchard Source, originally published in July 2016 and updated in July 2019.

In a cruel twist of fate, vigorously growing almond trees are the most likely to be infected by this disease. This includes trees with heavy crops that have been watered well and fertilized.

In fact, Dr. Brent Holtz, University of California Cooperative Extension pomology farm advisor for San Joaquin County, refers to hull rot as the “good growers disease” due to its tendency to be more severe in well maintained orchards.

No one knows why this is the case, but it is possible that it’s just a numbers game.

This theory suggests that more fruit become infected when the crops are heavy, and therefore, more toxins are released, resulting in the death of even more shoots and leaves than would occur on less healthy trees.

Factors That Increase Susceptibility

Two factors are key to the development of this disease. One is the level of nitrogen fertilization, while the other is the degree of irrigation.

A long-term study by Sebastian Saa et al at the University of California, found that the incidence of this rot increased in parallel with an increase in the amount of nitrogen applied.

When nitrogen is applied after the development of the kernels, it will be directed to the hulls, increasing the incidence of infection.

In addition, heavily irrigated trees are more susceptible to this disease.

Cultural Controls

Reducing the desirability of the hulls to the fungi will reduce the levels of colonization.

Your best bet to control this disease is to cut back on the amount of nitrogen and water that you add to your trees.

Reduced Nitrogen

A study by David Doll and Brent Holtz, two almond experts from the University of California, found that the most severely affected trees had nitrogen levels greater than 250 pounds per acre.

Rather than fertilizing your trees heavily, you should have a leaf analysis conducted in the summer to determine their optimal concentration of nitrogen.

The critical value is 2.2-2.5%.

Experts have found that nitrogen should not be applied once the development of the kernels is complete, typically in late spring.

Later applications go straight to the hull, and render the fruit more susceptible to infection.

You can resume nitrogen applications during the post-harvest period.

Reduced Irrigation

Reducing irrigation for two weeks starting at the beginning of hull split can drastically decrease the severity of infection.

If this is done properly, it can cut the severity of disease by 80-90%.

It is important that regularly scheduled applications continue, just with less water. Completely denying water to the trees for two weeks could be dangerous to them.

Arranging this reduction can be difficult, since the response of trees to a reduction in water will differ greatly in shallow versus deep soils.

Typically, you will only need to reduce the amount of irrigation that you provide by 10-20%. However, this calculation depends greatly on the soil that your trees are planted in, and the type of irrigation system that you use.

Commercial growers track the water status of their trees by using a pressure chamber to monitor midday stem water potentials (SWP), and then irrigate to maintain the stress levels of the trees between -14 and -18 bars during the hull split period.

Higher numbers indicate a greater degree of water stress.

Providing further instruction is beyond the scope of this article, but David Doll and Dr. Kenneth Shackle of the University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources Department describe how to use a pressure chamber in their article “Drought Management for California Almonds”.

Foliar Potassium Phosphate Fertilizer Treatments

Research by Dr. Jim Adaskaveg at UC Riverside found that foliar treatments with potassium phosphate could reduce hull rot.

He suspects this is due to neutralizing the toxic fumaric acid that leads to spur and leaf death when fungus is present.

Fungicide Treatments

The use of fungicides should be a last resort, since some of the leaf pathogens that are active when hull split occurs can develop resistance.

Dr. Adaskaveg also found that R. stolonifer only causes this infection during a brief period during the development of the nut.

The fungus enters the hulls via a point of injury, and they oblige by naturally wounding when they split.

This research identified that the highest incidence of infection occurred during this time when the hull only has a very small crack, a stage known as B2 based on information from the UC Integrated Pest Manual (IPM) manual published at The Almond Doctor.

Dr. Adaskaveg found that treating with two classes of fungicides at this stage can be highly effective on Rhizopus, but not on the other fungi:

- DMI (sterol inhibitor)

- Strobilurin

These fungicides act in concert with the above described cultural controls, and you can time their application with insecticide controls for the navel orange worm.

For Monilinia infections, apply these fungicides in the late spring.

A Note of Caution

Always use chemical products safely. Read the label and product information. Pay attention to any risk indications and follow the safety instructions on the label. If in doubt, seek professional advice.

A Disease That Afflicts the Most Well-Tended Almond Trees

Hull rot can cause devastating levels of damage to almonds during the hull-split period.

Ironically, because this disease is most prevalent on trees with heavy crops that have been well fertilized and irrigated, its onset may come as a disappointing surprise to many growers.

Two classic fungi are responsible for this rot, including the bread mold Rhizopus stolonifer and the fruit rot pathogen Monilinia. More recently, additional types of fungi have been implicated.

Manipulating the degree of irrigation and fertilization that you apply can significantly control almond hull rot, although fungicides are also an option of last resort.

Have you encountered hull rot in your almond trees? Were you able to control it? Let us know in the comments.

If you need general almond tree care information, consult our growing guide here.

And for more information about growing nut trees check out the following guides next:

© Ask the Experts, LLC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. See our TOS for more details. Uncredited photos: Shutterstock. With additional writing and editing by Clare Groom and Allison Sidhu.

very good information i want to see every day