Consolida spp.

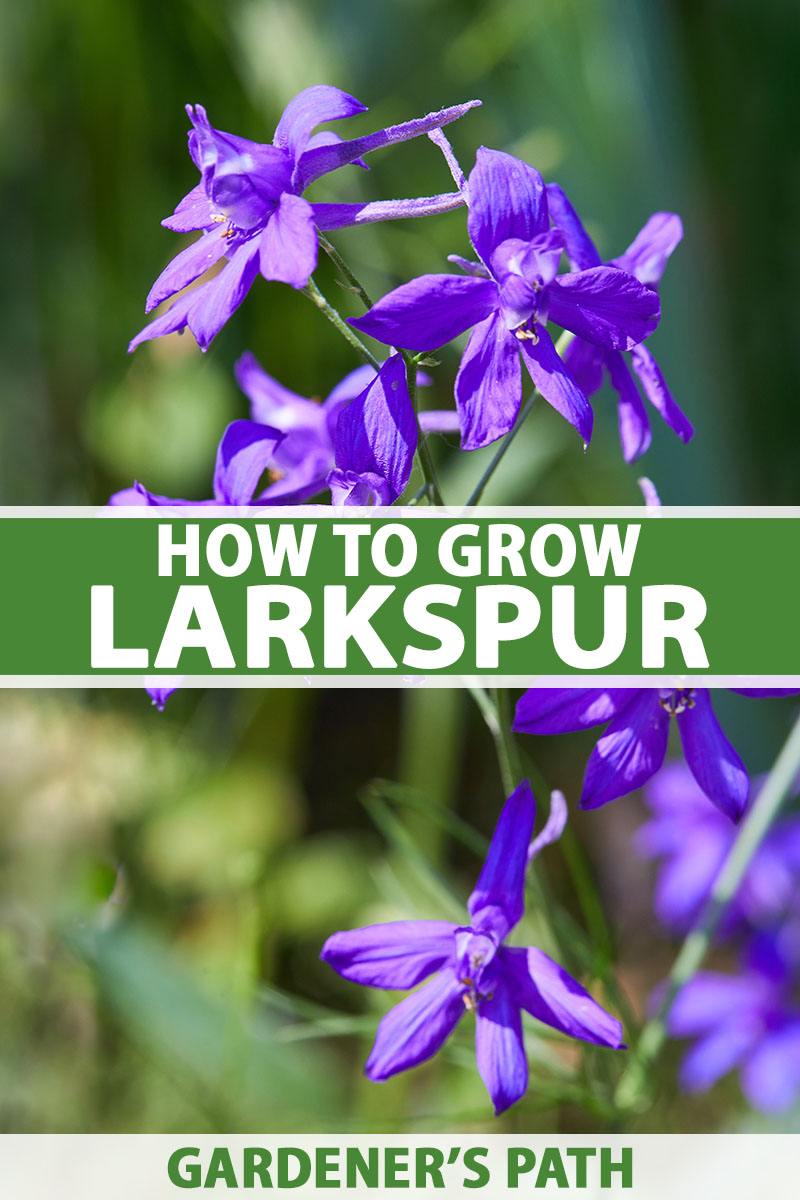

The best part of living somewhere cold and snowy is that the wildflowers that bloom after winter bring me a sense of delight I can’t quite describe.

Here in Alaska, it’s the wild roses, bluebells, and fireweed that appear in spring which make every cold day worthwhile.

In Montana, where I grew up, it was the arrowleaf balsamroot, lupines, and wild larkspur.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

Even if you don’t live in a state with freezing cold winters, you can still enjoy some of these magical flowers that lift the spirits come spring.

Like larkspur. Oh, how I love the tall spires, with their blue, violet, rose, and white blossoms.

If you’d like to grow this gorgeous annual in your garden, this guide has got you covered.

What You’ll Learn

What Are Larkspur? (And Are They the Same as Delphiniums?)

“Larkspur” is such a cheerful name, isn’t it? It makes me think of early summer, dewy mornings, and everything good and wonderful in this world.

An early mention of the name occurs in John Gerard’s book, “The Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes,” published in 1597.

Isn’t that spelling just epic?

Gerard refers to these as “Larks heele,” “Larks claw,” and “Larks spur.” All of these names reference the flower’s resemblance to the claw of a lark.

Can you see it?

The flower is also sometimes called knight’s-spur.

Of this bloom, Gerard writes, “The seed of Larks spur drunken is good against the stingings of Scorpions; whose vertues are so forceable, that the herbe onely throwne before the Scorpion or any other venomous beast, couseth them to be without force or strength to hurt, insomuch that they cannot move or stirre untill the herbe be taken away.”

I wouldn’t try flinging larkspur flowers at a scorpion or any other “venomous beast” to keep it from stinging me, but it’s fascinating to see what role the plant played in the 16th century, isn’t it?

Gerard also mentions similarities between the perennial delphinium and the annual larkspur, which “perisheth at the first approch of Winter.”

He writes, “Larks heele is called Flos Regius: of divers, Consolida regalis… It is also thought to be the Delphinium which Dioscorides describes in his third booke; wherewith it may agree: for the floures, and especially before they be perfected, have a certaine shew and likenesse of those Dolphins, which old pictures and armes of certain antient families have expressed with a crooked and bending figure or shape; by which signe also the heavenly Dolphine is set forth.”

“Flos regius” translates from Latin to “the royal flower.” C. regalis remains the botanical name for a species of larkspur today, and the genus Delphinium is a close relative.

Isn’t that too cool?

But here’s where things get tricky. Both larkspur and delphinium belong to the Ranunculaceae, or buttercup family.

Well known genera in the Ranunculaceae family include: Ranunculus, Consolida, Delphinium, Helleborus, Thalictrum, Clematis, and Aconitum.

It’s commonly thought that annual larkspur was once included in the Delphinium genus. But as you can tell from John Gerard’s 1597 publication, larkspur was deemed a Consolida species long before it was classified as Delphinium.

Yet gardeners everywhere often refer to both perennial delphiniums and annual larkspur by the same common name, “larkspur.”

Under the USDA’s classification report listing for the genus Delphinium, you’ll see it listed as the genus for all plants with the common name “larkspur” – whereas Consolida is saved for plants with the common name “knight’s-spur.”

To put it shortly and sweetly, larkspur, larks-heele, larks-claw, and knight’s-spur all refer to the same annual flower, which is sometimes listed in the genus Delphinium and other times as a Consolida.

There are forty species in the Consolida genus, and the ones most commonly grown are:

C. ajacis

C. ajacis is known as giant larkspur or doubtful knight’s-spur.

It’s native to the Mediterranean and southern Europe, and has naturalized in much of the United States and Canada.

C. orientalis

C. orientalis is commonly known as Oriental knight’s-spur.

This species is native to North Africa and southern Europe and it has naturalized in Vermont, Texas, Kansas, and Missouri.

C. pubescens

C. pubescens is commonly known as hairy knight’s-spur.

It is native to the western Mediterranean region and it has naturalized in North Dakota, Missouri, Illinois, and Tennessee.

C. regalis

This species is known as forking, rocket, or field larkspur, as well as royal knight’s-spur.

It’s native to western Asia and most of Europe, and it has naturalized in many parts of the United States and Canada.

C. tenuissima

Commonly known as long knight’s-spur, it’s native to Greece and has naturalized in Missouri.

As you can see, none of the above-described species are native to the United States. Instead, they were brought here from all around the world, from North Africa and the Mediterranean to Northern Europe and Western Asia.

But they sure thrive here, and they can add a gorgeous blush of color to any garden.

Cultivation and History

Sometime between 1550 and 1573, gardeners brought larkspur to England from Italy.

The flower made its way to the Americas not long after, and had found a place in gardens along the East Coast before the American Revolutionary War began in 1775.

From there, it naturalized all over Canada and the expanding United States.

As you might guess from these expansive growing habits, it’s a hardy plant: you can grow it in USDA Hardiness Zones 2 to 11, and it will self-seed readily after the blooms finish for the season.

These beauties grow to heights of 36 to 48 inches with a 12-inch spread of flowered spikes.

Read on to learn how to propagate these plants!

Larkspur Plant Propagation

Because it’s an annual that matures in just 77 to 84 days, the best way to propagate larkspur is from seed.

Though the same plants won’t come back year after year, these easily reseed – and will take over your garden if you let them.

Keep that in mind while planting and caring for these stunning blooms. If you don’t want them to pop up in unexpected places, deadhead the flowers before they form seed pods.

From Seed

Whether you’re planning to sow seeds indoors or outdoors, you’ll need to cold stratify them for the best shot at germination.

In colder climates, this happens naturally. The plant drops its seeds in the fall, and in the winter, rain or melting snow may wash the seeds into different areas of the garden.

To cold stratify your seeds, put them in an airtight container with some damp perlite, which you can find at the Home Depot.

Then, leave the container in the refrigerator for a week.

Trust me on this one. I once scattered seeds all over my flowerbed in mid-spring and waited for the magic to happen.

Since it never got cold enough to stratify the seeds, they didn’t germinate. What sorrow!

Indoor Sowing

For spring planting in Zones 2 to 5, you’ll want to start seeds indoors four to six weeks before the average last frost date in your area.

Use biodegradable pots instead of plastic seed trays, as these plants develop long taproots that don’t like being disturbed.

To sow, fill each pot with potting mix. Place two seeds inside each pot and cover with just 1/4 inch of soil.

Using a spray bottle, water the newly planted seeds and keep the soil moist until germination, which should happen in two to three weeks.

When the plants have two to three sets of true leaves, thin to one plant per pot. Wait until two weeks after the average last frost date in your area before you transplant them out to the garden.

To transplant, dig a hole in a location that receives six to eight hours of sun daily and set the biodegradable pot inside. Backfill with soil and water thoroughly.

Outdoor Sowing

In Zones 6 to 11, you can sow these seeds outdoors two weeks after your average last frost date – after you have cold stratified them, as described above.

Select a spot that gets at least six to eight hours of sun every day.

But keep in mind that if you live in Zones 7 and up, your larkspur would appreciate a couple hours of afternoon shade to keep cool during hot summer afternoons.

Sow two seeds apiece, half an inch deep, in holes 12 inches apart. Water thoroughly and keep the soil moist until germination, which will occur in two to three weeks.

Now here’s the neat thing about larkspur for those of you in Zones 6 to 10: you can actually plant it in the fall!

While the soil temperature outside might be chilly enough (55°F or colder) to cold stratify the seeds, you may still choose to stratify them in the refrigerator for two weeks before planting, just in case.

In early September, sow seeds outdoors according to the instructions above. The seeds will germinate and grow steadily for a month or so until the coldest weather hits.

If temperatures drop below freezing, the plant may turn brown and look dead. But it’s simply going dormant, saving up energy for when warmth returns.

Avoid watering the plant when it’s dormant, but remember to start back up again once you see new growth.

In early spring, the plant will grow new green leaves and emerge strong and tall, blooming through mid-spring, and into early summer for a repeat show with regular deadheading.

How to Grow Larkspur Flowers

As you might guess from its wild origins, larkspur can thrive in a wide soil pH range, but anything between 5.7 and 7.0 is ideal. These plants aren’t fussy, but they prefer moderately rich, moderately loose, well-draining soil.

Unlike their delphinium cousins, larkspur are hardy plants that don’t need heavy staking from the beginning. They’re actually pretty easy to care for after they’ve sprouted and grown a few true leaves.

If you do find that the stalks need support, drive a wooden stake down into the soil three inches behind the flower stalk and affix the stalk to the stake with a piece of stretch tie.

When the plants have two to three sets of true leaves, fertilize them with a balanced 10-10-10 (NPK) fertilizer according to package instructions.

Repeat this process once a month until the blooms open.

Once or twice a week, water the plants with an inch of water, depending on the amount of rainfall.

Before you water, check the moisture level by sticking your finger into the soil about one inch down. If you feel moisture, hold off on watering for another day or two. You want to keep them moist, but not waterlogged.

Also, take the time to lift the leaves and water underneath them instead of irrigating from above. This will help keep them dry and disease-free.

Growing Tips

- Provide staking if needed

- Water once or twice a week with one inch of water, as needed

- Fertilize every month with a general purpose 10-10-10 NPK fertilizer

Pruning and Maintenance

To extend the plant’s blooming period, prune away spent flower spikes promptly with a sturdy pair of scissors or gardening shears.

If you find any signs of pests or disease on the stalks, dispose of them far away from your thriving garden, or burn them.

That’s what I had to do with my aphid-infested delphinium stalks recently, and it helped keep the pests from coming back to my garden.

You can also prune a few spikes from each plant just after they bloom, and set the spikes in a vase for some indoor cheer.

Learn more about extending the life of cut arrangements here.

Like deadheading, this will encourage the larkspur to grow new spires.

If you’d like the larkspur to reseed itself, let the flowers go to seed toward the end of the summer.

After the seed pods open and drop their seeds, remove all dead vegetation from the flower bed.

Larkspur Cultivars and Mixes to Select

Whether you love blues, purples, or pinks, there’s a cultivar or mix available to suit your taste.

Here are a few of my favorite selections of larkspur to plant:

Blue Bell

Are you looking for a baby-blue bloom to raise your spirits every morning? Then ‘Blue Bell’ is the Consolida cultivar for you.

With sky-colored spires that reach four feet in height, looking at ‘Blue Bell’ will soothe any worry that’s troubling you.

Find seeds in a variety of packet sizes available at Eden Brothers.

Lilac Spire

True to their name, these purple flowers are the perfect bloom to set off white and blue-hued larkspur in your garden.

Or plant a whole bunch of them together for a startlingly stunning sea of lilac loveliness.

You can find seeds available at Eden Brothers.

Rocket Larkspur Mix

Looking for a classic Consolida to adorn your yard or garden? This rocket larkspur mix brings a delightful mix of color.

You never know what shade a plant will be until it blooms along with its sisters in a breathtaking display of pink, white, and lilacs spires.

Even better, rocket larkspur shoots up to six feet tall. Plant against a front-facing wall or fence for a dazzling show of color.

Find seeds available at Eden Brothers.

Managing Pests and Disease

Unlike its cousin, delphinium, larkspur are reliably pest and disease resistant.

As far as pests go, your biggest foes will be aphids and slugs.

If you see clusters of aphids sucking the life from your Consolida buds or stalks, spray them with a neem oil-based insecticide, like this one from Arbico Organics.

The next day, spray the carcasses off with a blast of water from the hose. Reapply the neem oil every few days, or anytime you see a sign of a living aphid.

Check out this guide to learn more about managing aphids in your garden.

Slugs and snails chew holes in the leaves but generally leave flowers alone.

To get rid of the squishy pests, spread Sluggo Maxx, available from Arbico Organics, around the plants. I love this stuff because it’s safe to use around pets.

Learn more about managing slugs and snails in this guide.

All parts of Consolida plants are toxic to humans and animals alike when ingested, so deer, rabbits, moose, and other critters avoid them.

If you live in the Pacific Northwest or a similarly rainy clime, watch out for various fungal diseases that can develop, like powdery mildew, root rot, and crown rot.

Powdery mildew leaves white moldy spots all over the leaves.

Monterey Liquid Copper Fungicide

To treat an infection, spray the plant with a copper fungicide product, like this one from Arbico Organics.

You can read more about stopping powdery mildew here.

Root rot and crown rot are caused by fungi in the Pythium genus and the bacterium Erwinia carotovora, which thrive in boggy soil, and these are a little more serious.

Telltale signs include leaves that turn yellow and stop growing. Pull affected plants and avoid replanting in the same location for at least a year.

The best way to steer clear of these diseases is to check for moisture before watering and do not irrigate overhead to avoid creating boggy conditions.

Best Uses for Larkspur Flowers

Larkspur makes a perfect addition to any wildflower garden or mixed border. Plant with corn poppies (Papaver rhoeas) for an especially satisfying blend of color.

These flowers do well in a container, too.

Next year I plan to sow them in whiskey barrels to put in the corners of my garden.

And of course, larkspur looks delightful when stalks are cut and put into vases, whether as part of a bouquet or displayed all on their own.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Flowering annual | Flower / Foliage Color: | Blue, purple, pink, white/green |

| Native to: | North Africa, Mediterranean, northern Europe, western Asia | Water Needs: | Moderate |

| Hardiness (USDA Zone): | 2-11 | Tolerance: | Some frost |

| Bloom Time / Season: | Spring-summer | Soil Type: | Moderately rich |

| Exposure: | Full sun to part shade (in hot climates) | Soil pH: | 5.7-7.0 |

| Spacing: | 12 inches | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | 1/4 inch | Companion Planting: | Corn poppies, lavender |

| Height: | 3-4 feet | Uses: | Borders, wildflower gardens, cut vases |

| Spread: | 12 inches | Order: | Ranunculales |

| Growth Rate: | Moderate | Family: | Ranunculaceae |

| Time to Maturity: | 77-84 days | Genus: | Consolida |

| Maintenance: | Low | Species: | ajacis, orientalis, pubescens, regalis, tenuissima |

| Common Pests: | Aphids, slugs | Common Diseases: | Crown rot, powdery mildew, root rot |

Welcome to La-la-larkspur Land

Though these flowers need a little extra care to get from pre-germination to the seedling stage, they will reward you for your efforts by breezing through the rest of their lives with hardly a care in the world on the part of the gardener.

You won’t regret your venture in the realm of the graceful, splendid larkspur.

Are you growing larkspur in your garden? Tell us your stories and ask us your questions in the comments below.

And don’t forget to check out these articles on growing flowers in your garden next:

Why do some delphiniums get purplish near the center of its leaves?