Are you looking to grow your garden in a smarter, more ecologically sound way? A way that reduces or eliminates the need for synthetic fertilizers, and is better for the environment and the soil food web?

It’s time to consider cover cropping. Part art and part science, it’s an environmentally friendly, rewarding way of providing your plants with natural fertilizers and nutrients, disease and pest management, and improved water penetration and retention.

Cover crops are also time savers, and they help gardeners to cut down on the tough manual work of erosion control, mulching, and weeding.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

It’s not just commercial farmers that benefit from this efficient soil management system – green manure is equally beneficial in small garden plots as well as the back forty!

This means you can make a real difference to both the health of your garden and the larger environment with the smart choice of cover cropping. It’s a natural for a happier garden and ecosystem!

Sound intriguing? Then kick back, relax, and join us for a look at the artful science of cover cropping – your garden and local biosphere will love this clean, chemical-free system.

Here’s everything we’ll cover:

What You’ll Learn

What Are Cover Crops?

Cover crops play a dynamic role in the farmer’s field as well as the home garden.

Typically planted between harvests or for winter protection, they’re temporary plants that provide nutrients for your vegetables and the soil they grow in.

But they also perform many other beneficial tasks throughout the season. The original term “cover crop” refers to their use as placeholders in empty, post-harvest beds since they completely cover the bed surface.

These are fast-growing species with known beneficial properties that are planted in rotation with cash crops to solve certain soil problems. At home, “cash crops” are the flowers, fruits, herbs, and veggies we like to grow.

They provide green solutions to common problems like soil loss due to erosion, depleted or nutrient-thin soils, and pesky weeds.

After growing for a predetermined length of time, the plants die back from winter temperatures or are mowed down, forming a protective mulch.

If a mulch isn’t desired, the alternative is to till under foliage and roots as a green manure, immediately adding nutrients and improving the soil makeup.

This all-natural system also reduces or eliminates the need for synthetic fertilizers, and plays a big role in pest management and weed suppression as well.

Cultivation and History

Throughout agricultural history, cover crops have been used to replenish nutrients and improve the tilth of overworked soils.

And notable farmers have long extolled the benefits of crop rotation to replenish and rejuvenate tired fields.

In the first century BCE, the Roman poet Virgil listed their virtues in his saga, “The Georgics.”

Specifically, he urged the use of “golden grains,” “slender vetch-crop,” and “lupins sour” after cash crops were harvested to quench the depleted, exhausted soil and give it repose.

And savvy founding farmer George Washington was known to rotate buckwheat and red clover with commodity crops such as wheat.

However, after centuries of use, the post-WWII era saw the green manuring practice all but die out. Instead, a new era of greater crop yields was introduced via the Green Revolution.

This was a new system that used designer, high-yielding seeds for improved harvests, plus the extensive use of water-based, synthetic fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides the new hybrids required for optimal performance.

It also employed industrial scale mechanization, like massive irrigation systems and the combustion engine tractors that are now so widely available to plow and sow vast tracts of land.

The convenience and enhanced yields provided by this system were quickly embraced by both the large-scale farmer and the backyard gardener.

Unfortunately, along with the boon to productivity, numerous problems lay hidden in the abundant yields.

One of the direct and most harmful consequences of this is the pollution that occurs every summer as pounds upon pounds of synthetic nitrates and phosphate leach into the runoff that ends up in our rivers and streams, then travel down the Mississippi River, causing dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico.

However, an interesting and benevolent side effect of the Green Revolution is that it also spawned the birth of the modern organic farming movement. While many embraced the new agricultural model, a vanguard of organic farmers again looked to the wisdom of cover crops to renew and replenish soils.

Today, more and more large-scale agricultural operations, both organic and conventional, are recognizing the cost-effective benefits, and incorporating crop rotation as part of their management model.

And of course, cover cropping at home has the same beneficial impact on our own gardens, as well as our immediate and extended environments.

Benefits

The benefits of cover crops are many and varied. Here’s a look at just how healthy your garden can be!

Easy Erosion Control

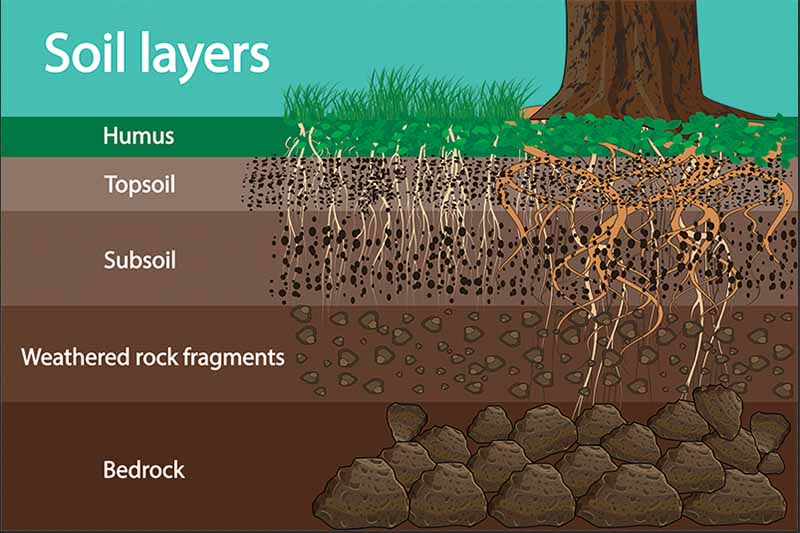

Harsh winter weather like rain, snow, and wind can quickly strip bare beds and fields of precious topsoil. Winter cover crops are one of the best options to defend against soil loss due to erosion.

Planted in late summer to early fall, winter cover provides a living mulch that’s either winter-killed, or cold hardy.

With winter-killed plants, the foliage dies back in cold temperatures and forms a mulch on top of the soil.

Winter-hardy plants survive the winter and push up new growth once daylight hours increase. Then, they’re tilled under in spring as a vibrant, green manure to enrich the soil for the next rotation.

These winter sowings form a healthy, living biomass of foliage and roots that keeps the soil firmly anchored in place even in heavy seasonal storms, retaining precious topsoil. Get the details on cold weather cover crops here.

A Biodiverse Environment

Healthy garden soils are host to numerous types of bacteria and fungi, many of which are beneficial to plant growth through the process of nutrient cycling.

These micro-critters feed on the carbohydrates plants release through their roots. And some, like the nitrogen-fixing Rhizobium bacteria, colonize roots to trade nutrients with the host plants in a symbiotic barter system.

Healthy microbial colonies attract beneficial insects and arachnids like beetles, earthworms, and spiders, who see them as food. And flowering crops like clover draw in pollinators, providing valuable early-season nectar for important flying insects like bees and butterflies.

In turn, the insects attract birds and small mammals, contributing to the diverse soil food web in your own backyard – with all standing by to service the fruit, flower, herb, and veggie crops that follow!

Enrich Soil Fertility

It may seem counterintuitive, but planting certain crops before or after your veggies can actually improve the soil’s fertility.

This is accomplished through the processes of nitrogen fixing, nitrogen scavenging, and nutrient cycling.

Nitrogen-fixing plants like beans, clover, lupins, and peas form a symbiotic relationship with the Rhizobium bacteria. These colonize the roots and are associated with the formation of nodules, in which the bacteria convert captured atmospheric nitrogen into forms the plant can use.

Nitrogen-scavenging crops like oats, radishes, and cereal rye trap free nitrogen in the soil that’s typically lost to leeching or runoff.

By preventing erosion, they help to keep nitrates in the soil where they’re helpful, and not in runoff where they can contaminate waterways, creating algae blooms and dead zones.

Nutrient cycling comes from the repetitive interactions of natural life cycles. After termination and tilling, plant materials break down, releasing valuable nitrogen and other elements like carbon, phosphorous, and sulfur back into the soil, reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers.

Decomposition is aided when plants release their sugars into the soil, which attract bacteria and fungi.

They in turn attract the earthworms that speed up plant breakdown, releasing nutrients back into the soil in bioavailable forms the next crop can utilize.

Improve Soil Aeration, Water Infiltration, and Water Retention

Plants with an abundant biomass typically have deep, complex root systems that improve aeration, water infiltration, and water retention.

They also help to prevent soil compaction and crusting, keeping it friable and better able to move oxygen and water.

A healthy biomass also traps surface water from rainfall, which increases root zone infiltration and reduces moisture evaporation.

Tilled-under plant residues also create a healthy, richly textured soil that absorbs water easily, transports it deeper, and holds moisture longer in dry times.

And plants with deep roots like forage radishes are effective at breaking up and aerating tough soils at deeper levels, so they’re lighter, easier to manage, and foster a healthy environment for the veggies that are planted the following season.

Soil Conditioning and Stabilization

The use of cover crops is one of the best, and easiest, ways to improve soil structure and stability.

Deep, thick roots help to break up clay soils and hardpan, the thick crust of earth that can form over finer, deeper layers of soil in newly ploughed beds.

And when used as green manure, the decomposition of plant residue adds soil organic matter (SOM) that conditions and builds tilth, improves fertility, and increases stability through the process of aggregation.

Aggregation is the arrangement of soil particles such as clay, sand, and silt with organic materials like glomalin.

Glomalin is the “glue” that holds aggregates together in a stable structure, and it is created exclusively by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), one variety of beneficial microbes that are attracted by the sugary carbohydrates released by plant roots.

Biofumigation and Pest Prevention

Certain cover crops, particularly the brassicas like canola, mustard, and forage radish, have the unique ability to prevent and destroy the cycles of some soilborne diseases and pests, including parasitic root-knot nematodes and various wilts like Fusarium and Verticillium.

This biofumigation property is a built-in defense against herbivores, and it happens when plants are chopped and tilled.

The chopping action causes plants to release enzymes that interact with glucosinolates and form a sulfur compound, isothiocyanate, that acts as a natural fumigant. Isothiocyanate is also what gives these plants their hot, pungent taste.

Along with the brassicas already mentioned, sudangrass, in the Grains and Grasses group described below, is also an effective biofumigator.

Weed Suppression

Effectively reducing weeds is a favorite feature for both the farmer and gardener. Here are a few ways cover crops do the job of weed suppression for you:

Fast-growing plants with a vast biomass can outcompete weeds for light, nutrients, space, and water, reducing their appearance by as much as 80 to 100 percent.

Some plants also have natural allelopathic properties. Active compounds known as allelochemicals that are produced by plants act like herbicides, impeding the growth of nearby germinating seeds and seedlings.

Buckwheat, canola, winter grains, and sorghum are a few crops with good allelopathic properties known to benefit growers.

A leafy green canopy is also effective at suppressing weed seed germination.

The green manure leaves absorb most of the available red light in the visible spectrum, which is needed by seeds to signal germination. Without the red light, seeds stay dormant.

And when the biomass dies back, it forms a mulch that keeps the soil shady and cool – again blocking the triggers needed to start germination.

Weed suppression is often most effective with crops grown in combination, like a grain and a legume.

How to Grow Cover Crops

Cover crops may be planted at various times from spring until fall, depending on how you want to use them.

Before planting, rake your garden beds or plots until the soil is level and smooth, removing any debris and stones.

Broadcast the seed according to the growing instructions and recommended rates for coverage for your selected variety. Seed packets will usually indicate what’s best if you purchase seed intended for cover cropping.

Lightly rake in the seeds, and water gently using a fine mist setting.

To ensure your plants get a good start, after sprouts are two to four inches tall, apply a balanced fertilizer such as 10-10-10 (NPK). For legumes, use a lower nitrogen formula like 5-10-10.

Water spring and summer plants regularly, and ensure winter crops receive adequate moisture if autumn rains are late.

To choose those best suited for your garden, determine the outcomes you’d like for each of the following questions as outlined below.

1. When Will They Grow?

Certain plants perform best in summer, such as buckwheat, cowpeas, millet, sorghum-sudangrass hybrids, and soybeans.

Others are better suited for winter, like crimson and red clover, forage radish, hairy vetch, winter rye, and winter wheat.

Choose the plants best suited for your region and the season you intend to grow them in.

2. How Long for Crop Maturity?

For cover plantings, crop maturity relates to the amount of time it takes from sowing seeds to when they’ll be killed.

To facilitate the planting of cash crops at the right time, summer cover crops and winter-hardy ones need to be chopped or mowed to end their growth. Freezing temperatures typically finish off winter-killed ones.

For maximum benefit, plants should be allowed to develop abundant foliage and possibly even begin flowering – but they need to be terminated before producing seeds.

When allowed to flower, some stems can take on a tough, fibrous texture that decomposes less readily. And you don’t want to till in seeds that could compete with the veggies to come.

Calculate the sowing date by counting back from the intended kill date for summer harvests, or the expected first frost date for winter plantings.

Keep in mind that it can take four to eight weeks for plants to establish healthy roots and ample foliage. Check the growing requirements for each seed variety that you’ve selected to tighten up planting times, and create a plan in your gardening journal.

When planning a sowing date for winter cover, remember that the soil starts to cool beginning in late summer in many regions, and this can slow plant establishment. If possible, factor in another week or two of growing time to counter delays due to cooling weather.

For spring and summer rotations with a tight cultivation window, fast-growing buckwheat and sorghum-sudangrass hybrids are always good options.

3. How Will Plants Be Terminated?

I know it sounds horrific, but premature plant termination is a necessary step with cover crops!

For the home gardener, the easiest method for killing plants is to mow them down with garden loppers, a lawn mower, or your string trimmer, cutting low and close to the surface.

After termination, the mown foliage can be left on the ground to form a mulch – which is very effective with no-till planting systems – or it can be tilled into the soil along with the roots, adding nutritious green manure.

4. How Long for Crop Residue to Decompose?

Plants decompose at different rates, depending on their structure.

For example, residue from plants with tender stems, such as buckwheat or peas, breaks down faster than those with thicker, harder stems like barley or sorghum.

Thick stems aren’t a problem if you want to use the residue as mulch, but for tilling, two to four weeks should be allowed for plants to decompose adequately before the next crops are planted.

5. What Food Crop Will Follow?

Finally, knowing what will be grown afterwards can help to determine the best cover species.

For example, heavy feeders like peppers and tomatoes benefit from following a green manure planting, particularly legumes like clover or field peas that add nitrogen back into the soil.

Once you’ve determined the purpose of your chosen plantings, select those species that fit your timeframe and the benefits you desire.

Growing Tips

Along with their multiple benefits, cover crops are chosen for their easy, fast growth. The following tips will help you to get the most from them.

- Mow and/or till under cover crops before seed heads form. Once seeds start to mature, flower stems can become hard and woody, and take much longer to decompose, and unwanted seeds may sprout.

- Allow two to four weeks for tilled plants to decompose before planting again.

- For short-term rotations, choose green manure plants that are tender and fast-growing like buckwheat or field peas.

- For long-term crops, pairing small grains such as barley, oats, and rye with a legume like peas or vetch combines multiple benefits for outstanding results.

- When in doubt, buckwheat is a great option to start with. Plant in spring or summer, allow it to flower, then mow and till – your natural soil enrichment practice is well under way!

For those keeners out there, a good reference book is always helpful in building new practices.

“Building Soils for Healthy Crops” by Fred Magdoff and Harold van Es is full of practical information on how to naturally foster healthy soil systems for abundant yields.

Building Soils for Healthy Crops

It’s available at Amazon.

Types of Cover Crops

Cover crops aren’t fancy plants, and they are readily available through seed houses, garden centers, and online sites.

We’ve curated a well-rounded selection, along with detailed descriptions, in our guide to the best cover crop varieties for the garden.

Cover crops fall into three main categories: brassicas, grains and grasses, and legumes. We’ll briefly cover each of these below, with recommended examples.

Brassicas

Brassicas are grown for their rapid cool-season growth, producing an abundant biomass that improves aeration, alleviates compaction, provides erosion control, and suppresses weeds.

They’re also excellent at scavenging nutrients, and aid pest management due to their release of isothiocyanates that act as a fumigant.

Common brassica species used as cover include arugula (Eruca vesicaria), canola (Brassica napus and B. rapa), mustard (B. hirta, B. juncea, and B. nigra), and forage radish (Raphanus sativus).

Grains and Grasses

The grains and grasses used as cover are those small-seeded species that germinate and grow quickly, producing large amounts of fibrous foliage and dense roots that provide erosion control, scavenge nutrients like nitrogen, build soil organic matter, and prevent weeds.

Grasses and grains are often mixed with legumes like clover or hairy vetch to double up the benefits, such as biomass production, nitrogen scavenging, soil conditioning, and weed control.

The species most often used for rotation include barley (Hordeum vulgare), buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum), oats (Avena sativa), triticale (× Triticosecale), annual ryegrass (Festuca perennis), winter rye (Secale cereale), and winter wheat (Triticum aestivum).

Legumes

Legumes are fast-growing forage species that develop an abundant biomass, reduce or prevent erosion, fix atmospheric nitrogen, and attract beneficial insects when in flower. They also work to disrupt disease, insect, and weed cycles.

Some legume seeds are also available pre-inoculated with Rhizobium bacteria, or you can purchase inoculant and apply it yourself, to ensure a fast, complete, and successful nitrogen-fixing cycle.

Commonly used legume species include cowpeas (Vigna unguiculata), crimson clover (Trifolium incarnatum) red clover, (T. pretense), hairy vetch (Vicia villosa), and field peas (Pisum sativum subsp. arvense).

In some applications, you may want to rotate a series of cover crops through your fields or garden.

Going Green

As you can see, going green with cover crops can achieve many things for your garden, from erosion control and nutrient building to pest and weed suppression.

Plus, utilizing more natural, less invasive ways of bringing food to the soil is a realistic way for us to contribute to a healthy environment. And a happy soil microbiome in your garden beds produces an abundance of tasty, happy plants!

It isn’t hard, and with a little planning you can ease your way into this practice and produce positive results starting in the first year.

Any questions about the art of cover cropping? Drop us a line in the comments section below!

And for more soil conditioning know-how, be sure to read these articles next:

What would be a good cover crop to plant in the spring to establish new beds that are very clay heavy and need to be broken up? I plan to plant turnips in the fall to overwinter and till in, but I would also like to work on amending the soil during the spring and summer as well. So I’m looking for a spring/summer cover crop. Our food actually did awful in those beds last year because of the heavy compacted clay, so we are gonna plant elsewhere while we work on amending the main beds. Thank you!

Thanks for your question, Kacey. There are lots of options when you’re dealing with clay. With the goal of breaking up the soil in mind, alfalfa is a nice option- its deep roots are a feature that will help to draw nutrients into the soil as well. Clover is another popular option, and most varieties are easy to establish. Buckwheat also does well, and like clover, it’s great for attracting native pollinators – but it will require summertime irrigation.

Hi, great article!

What do you recommend for covering a septic/leach field? We started with winter wheat, rye and clover but we really can’t turn things over much and no machinery. Thanks in advance!

Hi and thanks for all this info! I am just starting my permaculture project here in Spain (Girona). My problem is that the soil is really compact and dry, due to machine work and no rain), and heavy (clay). I would think it is quite fertile as I can spot some wild fennel and asparagus. My question is about using cover crops to decompact the soil : how can I plant them on this hard, dry soil? Can I just throw the seeds (I will use Vetch for this time of the year) and water well? Do I have to… Read more »

Sometimes tilling a soil to begin is going to be the best way to go! There are also some hand implements like a spike roller than you can run across the ground a few times if you don’t want to till too much. Then spread the seeds and see how well it works. If it’s too hot for the seed to germinate, perhaps use a mulch from straw or if a neighbor cuts their grass and you can use that as a cover over the seeds until they get a little more establishment. Also with you being in Spain, if… Read more »

I have learned that Hairy Vetch can be disastrous, though I think as you mentioned, if you don’t get them before they flower, they can be a bugger to get rid of. A farmer is currently battling a patch of HV in the middle of his field and it has been difficult to remove. Hairy vetch specifically has a pubescent leaf that makes it hard for chemicals to reach to affect. Common vetch is a better alternative and what people are trying to use. After reading this, I may shoot a few more suggestions his way to till it up… Read more »

Hi!

Its a wonderful article very informative.

Can you suggest the cover crops cocktail for the barren land winter season for Zone 9.

Thanks a lot

Please note that I just want to work on no till. So we need the cover crops to loosen the soil and improve the soil fertility Naturally

Regards

Hi Ikhlas, I’m so glad to hear you are working on improving your soil with no-till and cover crops! In your climate a mix of field peas, oats, and hairy vetch should work as a winter crop cover, such as this one from Arbico Organics, which is specifically designed as a soil builder. However, hairy vetch can be invasive so you may want to see if it’s a problem in your area before including that one. You could also include winter rye, winter wheat, barley, or daikon. However – since I don’t know the conditions on your land (alkalinity, water… Read more »

Thanks for sharing this informative post.

What if I grow my veggies within the living cover crop without termination? I couldn’t find any info. I am thinking that this could attract bees and distract insects, and the living crop could generate more nitrogen nodules for other soil organisms?

Hi Mark, yes you can certainly plant within the live crop and many who employ a no-till garden system do just that. However, depending on what you’re planting, competition for nutrients and water can be a concern. You might want to experiment a bit to see what delivers the best results… try planting a section with no crop termination and another section that’s gone to mulch. Give each section the same amounts of water and fertilizer, then let your harvest determine which was most successful. Could be interesting… Thanks for your question, and let us know how your veggies turn… Read more »

I planted a cover crop of winter rye in a field where I am going to grow wildflowers. I am now trying to figure out what I do with the rye so that I can plant the seeds. I get that I am supposed to either mow or till and let it decompose for 2 to 4 weeks. I would prefer the no till method in order that I don’t encourage all the previous weeds that were in the field to germinate. However, don’t I need to somehow eliminate the left over roots of the rye so that they don’t… Read more »

Hey Kate, the no-till method requires a bit of planning to ensure crops have decomposed in time for planting the next crop, your wildflowers. Once the is rye is winterkilled, mown, or knocked down, patience is needed for the breakdown process, which includes decomposition of the roots. However, you can aid the process by tarping the mown plants or laying down thick plastic. This ensures they’re completely killed, including roots, and speeds up decomposition by trapping heat and moisture. Once the surface plant matter is thoroughly broken down, rake the surface lightly to sow seeds. The roots should also me… Read more »

How we should start cover-crops on a weed covered land.without tillage

Do we need to remove weeds first or we can directly throw cover-crops seeds on the land as it is,

Hi Ikhlas, yes all competing weeds need to be removed before planting other crops.

This includes removing all topside growth and chopping or otherwise removing the roots.

Also, weeds should be removed just a day or two before planting a cover crop – this helps to prevent weed seeds already in the soil from germinating before your intentionally sown seeds.

Thanks for asking!

I am wondering it after I chop and drop the green manure would if be a good idea to put a layer of brown dead leaves on top? Would it help decomposes the green manure faster like a compost? I have raised beds. Thanks

Hi Diane, no adding a layer of brown onto the top won’t help the green material to decompose faster.

The best way to break down the green crop is to till it under and allow the soil, bacteria, and insects to do the job – or you can evenly scatter a thin layer of soil over the chopped foliage for faster breakdown.

Thanks for asking!