Platycerium spp.

When you hear the word “fern,” you probably picture those arching, lacy fronds growing in the humus-rich understory of forests.

You’re not wrong, but staghorns are also part of this ancient group of plants, which first emerged from swamps before humans populated the earth.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

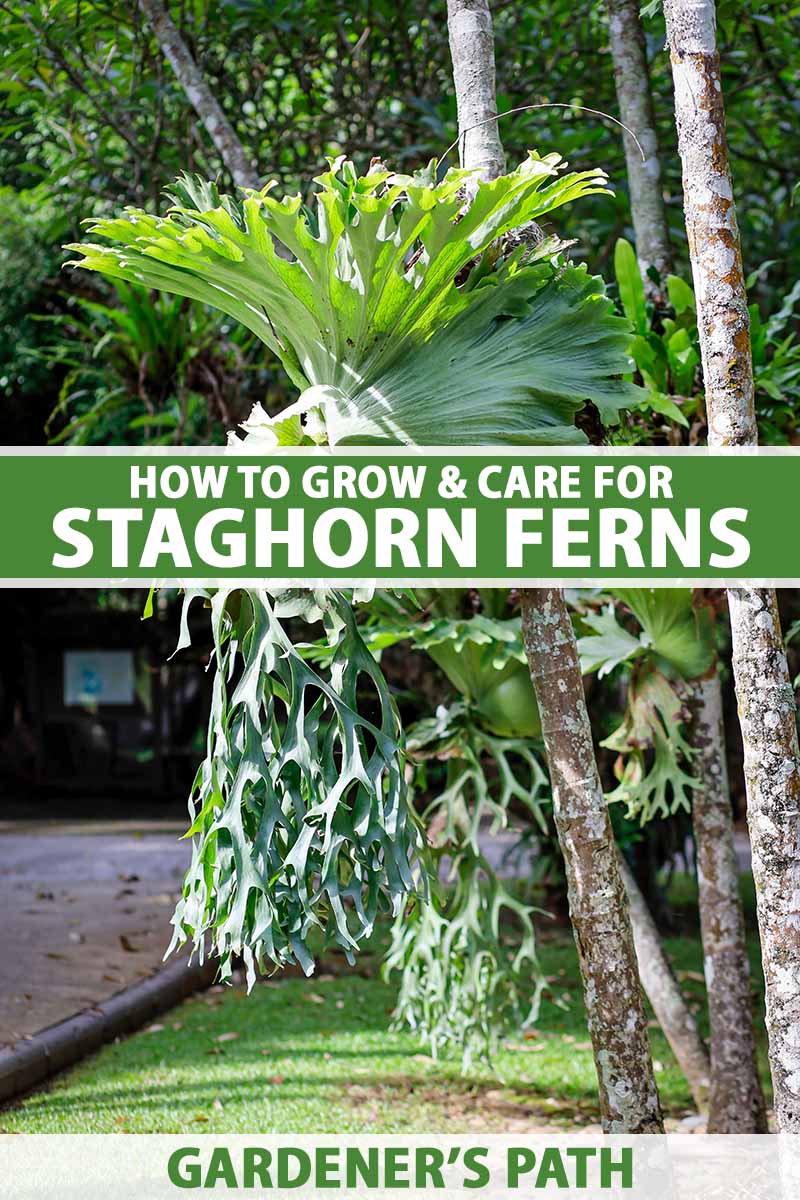

Staghorns and elkhorns, affectionately called platys, look like some kind of tropical prehistoric beasts clinging to a tree, and I can only imagine the first time a human stumbled on a massive specimen.

I bet their eyes bugged right out of their head. To me, some of the large, crowned species seem like they could be mistaken for lions, grasping the trunks.

In recent years, these ferns have become more and more popular as gardeners have come to appreciate the unique, striking appearance of these species.

I remember a year or so ago when Trader Joe’s briefly carried some staghorn ferns that could be bought for a song, and plant lovers were all abuzz.

It’s easy to see why: They’re fairly easy to care for once you master the art of mounting and remounting, but they often look like you put in years of effort to master the cultivation process.

If you’re ready to learn more about these dramatic plants, here’s everything we’ll go over in this guide:

What You’ll Learn

The first time I tried growing a staghorn fern, I was convinced I would kill it.

They just seem too unusual and exotic to be as easy to care for as, say, a pothos. Turns out, they’re pretty unfussy.

What Is a Staghorn Fern?

There are over a dozen species of ferns in the Platycerium genus that commonly go by the name “staghorn” or “elkhorn” fern.

Typically, those with thinner fronds are called elkhorns, and those with thicker ones are described as staghorns.

It’s pretty easy to see where these names come from.

The fronds distinctly resemble antlers, and the genus name is Greek for flattened (platys) and horn (ceras). There’s really no question about what makes these magnificent plants instantly recognizable, is there?

What sets the various species apart from one another is the amount, shape, and distance between the foliar fronds, as well differences in spore and pup growth.

The most commonly grown species in homes across the globe is P. bifurcatum.

There’s a good reason why this one is so popular: It’s much more forgiving and tolerant than some of the other species, which require very specific conditions to thrive.

Regardless of the species, all of these ferns are epiphytes, which means they grow attached to another plant. They’re not parasites, though. They only use the other plants as a structure to live on, and they don’t take nutrients from it.

They also show evidence of eusociality, which is when a group of organisms live and function in a cooperative group.

Ants provide the most well-known example of eusociality in nature, but a recent study published in The Scientific Naturalist by Victoria University biologist K. C. Burns, naturalist Ian Hutton, and evolutionary biologist Lara Shepherd, found that platys might be the first plants known to exhibit eusocial behavior.

All species also have basal fronds, which are round, heart-shaped, or kidney-shaped non-reproductive fronds that grow over the roots like a shield to protect them. These eventually turn brown as they mature, but they start out green.

Some of these basal fronds will curl upwards to catch food and water as it falls from the forest canopy. Over time, this falling debris forms a sort of compost that the plant uses as a nutrient source.

For the most part, the compost is made up of dirt and dead plant matter, but this plant doesn’t discriminate. Bugs and small dead birds or mammals can also contribute to this nutrient-rich substrate.

The antler-like fertile fronds that grow from the basal shields are called foliar fronds.

These can either be upright or drooping, and they may be long, flat, arching, and branching or forked into several segments along their length.

This shape is thought to be functional, serving to guide water down the length of the frond to the roots, kind of like a slippery slide.

The foliar fronds are green, but they can appear grayish-blue or silver because they’re covered in a fuzzy, dust-like coating of hairs called trichomes.

These hairs help capture moisture in the air for the plant to use, and they reduce the amount of water that evaporates out of the fronds.

The first time I bought a staghorn fern, I figured it had gotten super dusty, so I tried wiping the fronds “clean.” Don’t do that. The plants need these hairs.

Some staghorns produce a single rhizome but most send out pups that form their own rhizomes, so each plant or group of plants, also known as a colony, can become quite large. It’s not unheard of for them to grow over 10 feet wide.

There are three defined species groups for ferns in this genus, known as complexes: bifurcatum (bifurcatum, hillii, veitchii, and willinckii), Malaysian-Asiatic (coronarium, holttumii, grande, ridleyi, superbum, wallichii, and wandae), and Afro-American (alcicorne, andinum, elephantosis, ellisii, madagascariense, quardridichotomum, and stemaria).

Species belonging to these complexes, as described parenthetically above, share certain characteristics and common DNA.

Cultivation and History

Native to tropical rainforests and temperate regions of Java, New Guinea, Australia, New Zealand, Africa, South America, and Southeast Asia, staghorn ferns have been in cultivation for centuries.

The Veitch Nursery in Exeter, England was famous for their Platycerium during the 1800s, particularly the veitchii species, which was probably named for them.

In our homes, staghorns require attentive care to keep them happy, but certain species have become invasive outdoors in places like Florida and Hawaii.

This gives you an indication of the kind of environment this plant prefers: one that’s warm and humid. It can be cultivated outside in USDA Hardiness Zones 9 and up, but most gardeners opt to grow staghorns indoors.

If you want to see a particularly stunning example of this type of plant in North America, visit the Mendocino Coast Botanical Gardens in California, where they have a massive, half-century-old specimen that’s about 10 feet wide, and weighs about 250 pounds.

There are dozens of hybrids in cultivation too, including the popular P. x mentelosii (a cross of P. superbum and P. stemaria), P. x Lucy, P. x African Oddity (both crosses of P. alcicorne and an unknown parent), and P. x Silver Velvet (a cross between P. elephantotis and P. willinckii).

Propagation

Ferns can be propagated in many different ways, but as you’d expect from a plant that looks so different from other types of ferns, staghorns have unique propagation requirements.

From Spores

Just as with most ferns, staghorns produce spores that you can use to propagate new plants.

The process involves taking the spores from a mature plant when they’re ripe and placing them in a growing medium. Then, you nurture the spores as they mature.

To learn all about this process, check out our guide to propagating ferns.

Several species can only be propagated from collected spores because they don’t produce offshoots. We’ll talk about those in a bit.

From Seedlings

Most of us are going to buy little baby staghorns from the store or plant nursery initially. It’s the easiest way to get going.

When you purchase a staghorn fern, most of the time it will be potted in soil, though you can sometimes find them already growing on wood, in baskets, or in special epiphyte displays.

These latter options are usually older, larger plants, and you don’t need to do anything with them in terms of repotting or anchoring to a new substrate. Just start growing them as described below.

For those who purchase their staghorns in soil, you’ll have an extra step to complete. Let them develop in the soil for a little while until some of the basal fronds start to turn brown.

Now it’s time to move them to a better situation. While these ferns can survive in soil, they’ll do much better in a lighter, soilless medium, whether you grow them vertically or with the roots growing down into a medium.

You could replant them when the basal fronds are still green, but you’ll need to be extremely careful. These green fronds are young and easily damaged.

When you’re ready to move your baby staghorn to a soilless display, take it out of its container and brush or wash away all of the soil.

You can do this at any time of year, but fall is best because the plant isn’t yet growing its new fronds, which are easily damaged when they’re young as noted above.

Wrap the roots in coconut coir or sphagnum moss and secure them with twine, netting, or mesh.

Attach the little package that you just made on your chosen surface, whether that’s a piece of driftwood, the interior of a basket, or something like a moss ball holder.

These moss ball holders from Esterno, which are five and a half inches in diameter and available on Amazon, would make an adorable display for young platys.

After a few years, you’ll want to upgrade to something larger if you choose something of this size.

By Division

If you have a rambunctious little guy, go ahead and divide it up. This is a good job for the springtime.

To do this, carefully lift up the basal fronds and examine the roots. Look for a division with its own rhizome and fronds emerging from it. You want to be sure the pup has roots, fertile fronds, and basal fronds.

Use a knife to gently cut the pup, roots and all, away from the rest of the plant.

Now you can wrap it in a soilless medium as described above in the section on propagating seedlings.

How to Grow Staghorn Ferns

Staghorn fern fronds absorb water, and that’s a major way that these plants obtain their moisture, so they need to grow somewhere that’s humid. At the same time, they also need water at the root level.

Imagine one of these plants in its natural environment – it receives rain regularly, and the humidity level is generally around 70 percent.

If you grow yours in less humidity, you’ll need to water more often to make up the difference. You can also use a humidifier, mist the leaves regularly, or grow them in a humid room like the bathroom.

If you’re growing in soil, you need to be extremely cautious about watering. Wait until the fronds have started to droop slightly and the soil feels dry on the surface and up to an inch down before watering.

Growing without soil? Water whenever the moss or whatever medium you’re using dries out. It doesn’t need to stay consistently moist, but it’s really difficult to overwater a mounted plant since the water just runs right through.

I know it probably feels weird to let a fern become so dry, but the thick leaves can store a lot of water, and the roots are prone to rot. If in doubt, water less often than you think you should.

However, staghorns seem to do better with more water if it’s unchlorinated, so the risk of providing too much water is likely more of an issue related to chemically treated municipal water with too much chlorine rather than too much actual water.

Rain water or reverse osmosis filtered water with a low pH is best.

If you’re growing yours outside, be sure to bring the plant inside before temperatures drop below freezing, or as temperatures approach whatever limit your particular species can withstand.

Most species can survive brief periods with temperatures ranging down to the mid-20s, but not all. And anything but much longer than a few hours of extreme cold will kill them.

Most species need bright, indirect light to thrive. Some can tolerate more or less light, and a few species can even handle direct sun for a few hours.

Gardeners cultivating staghorn ferns outside might need to provide protection using shade cloths during the winter when deciduous trees lose their leaves. Just keep an eye on your plant and gauge how much sun it’s receiving throughout each season.

If you want to take your plants outside during the summer, assuming they aren’t known to become invasive in your area, go for it. Just be sure to bring them back in if temperatures in the evening are going to dip below 40°F.

You might want to harden them off to the outdoors gradually unless you’ve cultivated your indoor plants in lots of light. That way, they’ll have time to acclimate to the brighter light you typically find outdoors, even in shady spots.

If you’ve ever hardened off seedlings, it’s the same process.

Take the staghorn and put it where you intend to grow it, and leave it there for an hour. The next day, make it two hours. Keep adding an hour until you have a full eight hours, and then you can leave your plant outdoors full-time while conditions permit.

During the spring and summer, fertilize once a month with a mild, balanced liquid fertilizer when you water the roots. In the fall and winter, when the plant is dormant, feed once every three months.

I’m a fan of Dr. Earth Pump & Grow because it comes in a handy pump bottle, is mild and balanced, and is made using recycled scraps from grocery store waste.

Snag a 16-ounce bottle at Arbico Organics.

You might have heard of people feeding their platys by placing a banana or banana peel at the base, and you can certainly do that if you want.

I find it works better on outdoor plants. Indoors, it just smells and attracts bugs. It’s also not a complete food source, so you’ll want to feed with a regular fertilizer as described above as well.

When it comes to choosing a mount, you’re only limited by your imagination and the size of your fern. Most people opt for wood planks, with redwood being particularly popular. You can also use baskets, pieces of cork, driftwood, or coconut husk boards.

You can even find pre-made wood boards that look like miniature pallets. These give you lots of spots to secure your plant and they can be quite large and sturdy.

Growing Tips

- Fertilize once in fall and again in winter, monthly in spring and summer.

- Humidity around 70 percent is ideal.

- Allow the medium to dry out between watering.

Pruning and Maintenance

Now and then, a frond will be damaged or one will dry up and wither. Remove these at the base with a clean pair of scissors or clippers. Otherwise, no additional pruning is necessary.

Remounting, which is the epiphyte version of repotting, is often necessary and should be done in the late fall, just before the new basal fronds start to emerge.

If you see roots growing out of the medium, it’s time to remount.

To remount, remove some of the media from around the roots. You don’t need to take it all away from the roots, just knock away anything that’s loose.

Add more moss, coir, or whatever you’re using. The roots should be padded with a good inch or two of the medium so they have room to grow, and so there’s plenty of medium to catch the water and nutrients you provide.

Then, resecure the root ball and medium with your chosen material (twine, netting, etc.) and place it on or in your support.

Species and Cultivars to Select

When it comes to picking a staghorn fern for your collection, most of the time, you’re going to come across P. bifurcatum species unless you go to a place that specializes in unusual and rare plants.

If the seller doesn’t specify, assume that it is this species.

In addition to P. bifurcatum, the following list includes some of the more common options that work well as houseplants:

Andinum

P. andinum is quite distinctive, with a raised crown of narrow basal fronds and narrow, heavily segmented and lobed, hanging fertile fronds.

These fronds also feature prominent veins. This plant is typically longer than it is wide, and individual fronds can grow up to five feet long.

This is the only plant in the genus native to the Americas, and it grows in the Andes Mountains in Peru and Bolivia. It’s commonly known as American staghorn.

This fern needs to dry out completely between watering and must have good ventilation. It’s also extremely challenging to grow from spores.

Bifurcatum

As we mentioned, this species is the most common type grown as a houseplant, hence the moniker common staghorn fern.

It grows about three feet tall and wide, on average, though it can be much larger.

The basal fronds are heart-shaped, while the foliar fronds are strappy and forked, each growing up to three feet long.

All species in the bifurcatum complex including this species as well as P. hillii, P. veitchii, and P. willinckii form spores on just the tips of their fronds.

‘Netherlands’ has foliar fronds that grow upright before curling slightly at the ends. It can tolerate direct sun. This is the most common P. bifurcatum cultivar.

If you want to give it a go, grab a live ‘Netherlands’ plant in a three-inch pot from Wellspring Gardens on Amazon.

‘Forgii’ has narrower fronds that are dramatically forked. ‘South Seas’ features long fingers.

Coronarium

P. coronarium hails from Southeast Asia and the East Indies, where it grows on trees tall enough to accommodate its incredibly long foliar fronds, which can reach up to 15 feet long.

This is another challenging species to grow, but once established, it’s much more hardy than other species. In the wild, in its native Malaysia, Thailand, and Taiwan, the plants usually form rings around the trunk of their host tree.

The basal shields become extremely corky and thick, with long, strappy, branching fertile fronds. Young basal growth has distinct, raised veins.

This species grows separate fertile and foliar fronds with thick stalks. This is something that sets it apart from other species, which form spores on every fertile frond.

This species is considered one of the most difficult to grow.

Elephantotis

The elephant ear or Angola staghorn, P. elephantotis, isn’t for beginners, or for anyone who keeps the thermostat set low.

It won’t tolerate temperatures below 60°F and prefers to be in the 80 to 90°F range.

The massive, heart-shaped shields die in the spring and the dead edges should be removed to promote a tidier appearance and upright growth in the newly emerging shields.

The wide, veined, foliar fronds are deep green and don’t branch or fork at all. They truly resemble green elephant ears.

This species is sensitive to overwatering, but it will perk right back up if you let it wilt between waterings. It also prefers brighter light than most species.

Up for a challenge? Bring home a three- to eight-inch-tall platy pachyderm from Wellspring Gardens, available via Amazon.

Grande

Grand staghorns (P. grande) are just that, with their wide, fan-shaped basal fronds acting as a base for narrow, drooping, unbranched foliar fronds that can grow up to six feet in length.

Though this species doesn’t form pups, a single plant can spread up to four feet wide.

This is a difficult species to grow, unable to tolerate temperatures below 40°F.

It can’t tolerate too much heat, or too much or little water, or too little humidity either. It also is a solitary species, meaning it only has one rhizome, so the only way to propagate it is by collecting spores.

For these reasons, you won’t often find giant staghorns in stores.

Often mistaken for P. superbum, they were once classified as the same species. P. grande is nearly extinct in the Philippines, where it’s originally from.

Hillii

The broad foliar fronds on P. hillii only grow to two or three feet long, but what it lacks in dramatic length, it makes up for in style.

With round or heart-shaped basal fronds and upright, forked fertile fronds, it bears an uncanny resemblance to a mounted set of antlers.

Some cultivars have extremely pronounced veins, and some have long, narrow fingers while others have short, wide fingers on the broad fronds.

It’s a robust, tolerant species that usually sends out copious amounts of offshoots.

‘Hula Hands’ has particularly short and wide fingers, while ‘Jimmie’ has long fingers.

Stemaria

Also known as the triangle staghorn, this African species has large, round, wavy basal fronds and shiny, wide fertile fronds with long fingers.

Each finger can be half as long as the overall length of the main frond. These fingers usually fork multiple times on each frond.

This species does best in lower light. Look for cultivars like ‘Laurentii,’ which can tolerate brighter light, ‘Hawke,’ with its extremely wide foliar fronds, and ‘White,’ which has extremely hairy fronds that almost appear white on the underside.

Superbum

This Australian native is gorgeous, though it’s a bit more difficult to grow than some other species. It has naturalized in Hawaii, but elsewhere with less-than-ideal conditions, it doesn’t always do so well.

If you do manage to keep it happy, you’re in for a real treat. Hobbyists prize this staghorn.

When it’s young, it looks a lot like P. grande – and was once classified as such. The foliar fronds are light green and can grow up to three feet wide and six feet long. The leaves are heavily lobed with lots of long fingers.

As it matures, the shield fronds are also heavily lobed and deeply veined, and may grow up to four feet tall and wide, with raised edges.

‘Cabbage’ and ‘Cabbage Dwarf’ are the two most common cultivars. Both have compact growth that makes them appear cabbage-like. The only difference is in their size.

Veitchii

If you want a staghorn that can handle full sun, this is a good species to choose.

P. veitchii or the silver elkhorn can tolerate full sun and temperatures up to 120°F, as may occur from time to time in its native Australia.

It’s petite, with extremely thin and strappy, finger-like fronds covered in so much hair that they appear nearly silver. The fertile fronds grow upright in bright sun and are more weeping in lower light.

This is one of the most drought-tolerant species, so it won’t scold you if you neglect your watering schedule a bit.

‘Lemoinei’ has brighter green fronds and does well in lower light, though it’s less tolerant of drought. This is probably because those lighter fronds have fewer hairs, so they’re less able to gather moisture.

The ‘Silver Frond’ cultivar has fronds that are more distinctly silver than those of the species plant and, yep, it’s extremely drought-tolerant.

Sound enticing? Bring one home in a three-inch pot from Amazon.

Wandae

P. wandae is known as the queen staghorn, and for good reason.

It’s massive, with a tall crown of upright shields that can reach four or five feet. The fertile fronds hang down and are deeply lobed and rippling.

Sensitive to cold, this Papua New Guinea native needs to be cultivated somewhere with temperatures between 60 and 100°F.

It doesn’t send out pups, and there aren’t many cultivars available, so these can be hard to find.

Because of its size, this staghorn really does better outdoors than it does inside. Plus, more than other species, it seems to need gentle wind to help it develop strong growth.

Willinckii

The Java staghorn comes from Australia, Java, and other parts of southern Asia.

A member of the bifurcatum complex, this fern has tall, deeply lobed shields that rise like a crown. The fertile fronds grow up to six feet long, and they’re narrow and twisting.

‘Bloomei’ has prominent veins and fronds that start out quite narrow but flare dramatically at the tips.

However, note that ‘Bloomei’ is possibly a P. hillii cultivar – the jury is still out. The two species are extremely similar, but this cultivar appears to have more in common with the willinckii species. Isn’t botany fun!?

‘Java,’ ‘Scofield,’ and ‘Little Will’ are some other common cultivars. ‘Scofield’ is a particularly tough and tolerant cultivar, so it’s excellent to grow if you’re just starting with this plant.

Managing Pests and Disease

Given the right environmental conditions, you probably won’t run into pest or disease problems too often. Catch problems early, and they’ll rarely harm your plant much at all.

Insects

There are really just two bugs to watch out for. Mealybugs are the most common, followed closely by scale.

Both insects are in the order Hemiptera and both feed on the sap of plants, causing wilting, yellowing, and browning of foliage.

Mealybugs

Mealybugs are flat, sap-sucking insects that are often mistaken for a sign of disease rather than a pest.

That’s because they don’t move very quickly, they tend to cluster in groups, and many species have a white, waxy coating that makes them look a lot like a fungal disease.

On platys, they’ll cluster at the base and drain the sap from the plant. Don’t let them!

Patient gardeners can use a cotton swab dipped in isopropyl alcohol to wipe each insect. This removes the protective covering and eventually kills them.

For more tips, read our comprehensive guide to this common pest.

Scale

Like mealybugs, these pests are often mistaken for a disease or some type of funky growth on a plant.

They’re flat, slow-moving, and cluster toward the base of the plant where they feed on the sap, using their piercing-sucking mouthparts.

You can scrape these pests off using a butter knife, or wipe them with rubbing alcohol as described above.

Our guide has more information on identifying and dealing with scale.

Disease

Platys like a lot of humidity and moisture, but there can be too much of a good thing. Overwatering or poor air circulation can invite fungal issues.

By the way, don’t panic if the underside of the leaves starts to look brown. These are the spores. If the upper side starts to turn brown, it’s usually due to too much light or too much water.

Black Spot

This disease, caused by fungi in the Rhizoctonia genus, is sneaky.

It starts out as tiny black spots at the base of the shields that are hard to see because of the overlapping nature of the basal fronds. These spots eventually begin to turn mushy. Before long, your plant is toast.

The fungi that cause this disease just love a warm, wet, humid spot, so watch out.

If black spot does come to visit your platy, grab yourself some Mycostop tout de suite! Better yet, keep some on hand. It’s incredibly effective against many of the worst fungal jerks.

Arbico Organics carries it in five- and 25-gram packets. Follow the manufacturer’s directions to the letter, and your plant should bounce back in no time.

Root Rot

Root rot is common in many plant species. In staghorns, it’s most common in plants that are grown in soil.

Overwatering often smothers the roots, and they essentially drown. The solution there, of course, is to water less and make sure your pot provides excellent drainage.

In mounted plants, root rot is usually caused by oomycetes or fungi rather than physically drowning the roots. Pythium and Fusarium species are the usual culprits.

It’s hard to see initially because the symptoms start at the roots, turning them brown and mushy. Above the roots, the plant wilts and stays wilted, even after watering.

Once again, get yourself some Mycostop and get to work.

Best Uses for Staghorn Ferns

While they can make cute potted specimens, these are really plants that beg to be mounted on a wall or tree.

They look incredibly interesting, and they’ll be happier if they’re grown that way.

Quick Reference Growing Guide

| Plant Type: | Evergreen epiphytic fern | Flower/Foliage Color: | Medium green, silver, blue, dark green |

| Native to: | South America, Africa, Asia, Oceania | Maintenance: | Moderate |

| Hardiness (USDA Zones): | 9-12 | Tolerance: | Some drought |

| Bloom Time: | Evergreen | Soil Type: | Sphagnum moss, coco coir; loose, rich. loamy for potted plants |

| Exposure: | Full shade to full sun, depending on species | Soil pH: | 5.5-7.5 |

| Time to Maturity: | 10 years | Soil Drainage: | Well-draining |

| Planting Depth: | 2 inches of medium surrounding roots | Uses: | Mounting, potted houseplant |

| Height: | Up to 20 feet | Order: | Polypodiales |

| Spread: | Up to 15 feet | Family: | Polypodiaceae |

| Growth Rate: | Slow | Subfamily: | Platycerioideae |

| Water Needs: | Moderate to high | Genus: | Platycerium |

| Common Pests and Diseases: | Mealybugs, scale; black spot, root rot | Species: | Alcicorne, andinum, bifurcatum, coronarium, elephantosis, ellisii, grande, hillii, holttumii, madagascariense, quadridichotomum, ridleyi, stemaria, superbum, veitchii, wandae, wallichii, willinckii |

Mount Up, Staghorn Lovers!

Have you ever seen a wall full of platys? They’re so cool and so striking.

It’s like a living piece of art, but that extra impact doesn’t really require any extra effort. It’s just a matter of understanding how to keep staghorns happy.

I can’t wait to hear about your platy-growing adventures. What species are you growing?

Did you nab yourself your very first bifurcatum? Or are you opting for something a little different? Maybe you’re challenging yourself with an elephantotis? Fill us in via the comment section below.

Crazy about ferns? Me too!

If you’re curious to learn more about these prehistoric plants, you might want to give a few of our other guides a glance. Here are some good ones to start with:

Kristine, thanks for the most beautiful pictures and info about all the different stags and elks etc, I just have two kinds and love ❤ them.But I have been very ill lately and my husband has been taking care of them.I just found out they have black mold.stay tuned.thank you so much loved your article.

Thank you for the kind comments, Brook. I love staghorns, too. I hope both you and your plants feel better soon. Do you know what kind of fungal issue you’re dealing with? Is it root rot or black spot?

This is the most informative article I have ever read on Staghorn Ferns. Thank You. I am still trying to find out if indoor Staghorns like a lot of air circulation, as a general rule I run an oscillating fan on all my house plants including my ferns on and off during the day and they are misted several times a day and are setting on pebbles above the water line in saucers for extra humidity.

Hello! Thank you so much for the kind words. Air circulation is almost never a bad thing. However, staghorns prefer high humidity, and fans can reduce humidity. Having said that, if your plants look healthy with lush, green fronds, and are growing well, I’d keep doing what you’re doing.

I really want to “mount up” (literally) ;-). I’m into Aroids and recently received a platycerium from a friend (small plants, don’t know the species). But I do know they should be mounted in a special way. There seems to be a “up” and “down” side. How can I spot which way I must mount them?

Hi Coen, welcome to the wild world of platys! It can be hard to tell with smaller plants, but you want to part with the longest antler fronds on the top, with the fonds growing up. Since young plants don’t usually have basal fronds, you can’t use them as a guide. But if they’re present, they should be cupping the long, upright antler fronds on most species. Some species, like superbum, have pretty distinct upper and lower fronds, but you can’t make these out until they’re older. I mounted one sideways once and it eventually righted itself. Honestly, I just… Read more »

Hello…We have a fairly large staghorn that is outgrowing its wire basket. We’d like to put it into a larger basket. The current basket is covered with older shields. Can we line the larger basket with moss and/or soil and just drop in the old basket? This would cover the outside shields. If this is a bad idea, what is the correct way to transfer? Thanks for any advice! Enjoyed your article.

Hi Nancy, you could line a larger basket and then leave the staghorn in the existing basket, but I’d recommend cutting out the bottom or some of the side wires if you can to allow the roots better access. It depends on how wide the openings are in the basket. Those roots need to anchor the plant, and if they can’t get out of the basket, they won’t be able to do that. I always lean toward doing my best not to disturb the shields and roots.

Enjoyed this Post. Learned a lot.

My Staghorn is reasonably big at 2 ft wide 3 ft long.

But it only has 3 spots that fronds come out.

Is there a way to make more?

(it looks extremely sparse.)

Hi Ken, thanks for the kind words. I don’t know of any way to force growth where we want it, but I’ve had staghorns that looked sparse in the past. It has always been an issue of not enough sunlight. Though you should introduce them gradually over a week or so, most staghorns can tolerate more sun than we expect. Try moving your plants to a sunnier spot.