Whether you’re new to gardening or a veteran green thumb, growing your own plants can be one of life’s most rewarding experiences.

We link to vendors to help you find relevant products. If you buy from one of our links, we may earn a commission.

It’s a powerful practice, no doubt. After all, the intentional cultivation of plants allowed our species to switch from hunting and gathering to farming and settling, which in turn led to a little thing called human civilization.

Science, technology, medicine, writing, the arts, and everything else that we developed thanks to specialized labor and large populations, we owe it all to flora.

Without cultivated plants, modern-day life and the world as we now know it wouldn’t exist, for better or worse. Personally, I like to think it was a significant upgrade.

In short, to purposefully cultivate plants is to be human.

And however complicated it may seem to a layperson, growing and caring for these organisms is pretty simple, once you understand how it works. Not always easy to execute, but simple to gain a grasp of.

This guide boils down plant parenting into 10 easily digestible lessons. You’ll gain some solid know-how that you can use to grow pretty much any species you’d like, albeit with a little supplemental research.

Here’s a heads-up, though: you just might discover that this is your new favorite hobby. Make room in your schedule, budget, and thoughts accordingly.

Here’s the syllabus:

Growing Plants 101

Lesson 1: Plants Are Alive

Since they lack faces and (usually) don’t move, it’s easy to sometimes forget that plants are living things.

But just like people and animals, they start out as babies, grow into adults, reproduce, grow old, and eventually die. Their requirements for staying alive are also pretty similar to ours.

What do humans need to survive? Well, we need food, water, air, and protection, and we meet these needs by eating, drinking, breathing, and taking shelter. In the modern day, we also wear clothes, nudists and streakers aside.

Plants also need these things, they just acquire them in different ways.

They make their own food from carbon dioxide, water, and sunlight in a process known as photosynthesis, they absorb water via osmosis, they take up oxygen via gaseous exchange, and they remain shielded from extreme temperatures, winds, and sunlight by growing in the right place.

By consciously remembering that these organisms are alive, you’ll be reminded of their needs, and you’ll also develop some serious empathy for them.

I recall a coworker of mine who was so protective of her garden specimens, she’d throw her soil knife at any hungry rabbits she saw. Thankfully, her aim was never true, but her empathy was commendable.

Treat your plants right, and they’ll treat you right. Here are some benefits that you’ll receive from your botanical friends:

Increased Oxygen

Flora will take up carbon dioxide, turn it into energy for themselves, and release oxygen into the air.

Free Food

When you grow your own berries and other types of fruits, vegetables, and herbs while avoiding pesticides and artificial chemicals, you can end up with some really fabulous edibles.

Free Medicine

Some species are medicinal, and can be used like you would medicine from a store. After all, many medicines are simply synthetic versions of what you’d find in nature.

Shade

Wide-spreading landscape trees come to mind. Along with protecting us from the elements, their canopies provide homes for many delightful insects, birds, and small mammals.

Tranquility

It goes without saying that a gorgeous landscape is quite peaceful, especially if it’s your own. In the garden, you can let your mind do some stress-free wandering for a bit.

Exercise

Walking, stooping, digging, and hauling in the garden are all fantastic physical activities. And if you go at your own pace, you can enjoy gardening for many years, often well into old age.

I could go on. But I’m sure that you’re chompin’ at the bit for some plants right about now…

Lesson 2: Acquisition

There are three ways to acquire new plants. You can transplant established specimens, sow seeds, or propagate new plants from existing specimens.

I suppose you could also buy or inherit the land that they sit in, but I’m not qualified in telling you how – I myself own no real estate.

Transplanting is simply moving a grown plant from one growing site to another. It’s the quickest and easiest way to end up with some ready-to-flaunt vegetation, and generally, spring and fall are the best times to do it.

You’ll want to give your transplants ample protection and TLC until they settle in and become established, i.e. grow enough roots to acquire the necessary resources in their new homes.

For seed sowing, harvested seeds are put in soil and cared for until they germinate. Sometimes, seeds need pre-treatments such as physical scarring or exposure to extreme temperatures to be able to germinate.

After germination, the seedlings are cared for further until they reach transplanting size, if they need to be moved elsewhere. Otherwise, they’re nurtured until adulthood.

Since seeds are a result of sexual reproduction, you could end up with some neat variation from the parent that they were taken from. However, this method of propagation is usually the most time-consuming.

Other types of propagation involve a form of asexual reproduction where additional plants are created from the vegetative structures of a parent, creating genetic clones.

This practice takes advantage of plants’ inherent ability to heal and grow new tissues, and leaves you with offspring that are genetically identical to their parents – perfect for producing uniform specimens.

There are many methods of asexual propagation, each with its own pros and cons.

You can take cuttings from a plant’s leaves, stems, or roots, you can surround intentionally damaged tissue with soil to promote rooting via layering, you can combine parts of two different specimens to make a new one via grafting or budding, and you can even divide an existing plant into multiple, ready-to-transplant pieces!

Once acquired, your propagules are nurtured until they grow into transplantable size.

But regardless of whether you choose transplanting, sowing, or propagation, how does one actually obtain a plant, or at least have access to the seeds and/or propagate-able bits of one?

Well, you can buy them from stores, online vendors, or festivals. You can snag some from plant swaps, trade shows, or even fellow green thumbs. You can use your own specimens, or those that you see when you’re out and about – with permission, of course.

You can even take in “rescues,” or specimens that have been cast aside or thrown away.

These guys can often be in pitiful condition, offering the compassionate gardener a chance to test their skills at reviving them.

Lesson 3: Climate

Acquiring a living plant is all well and good, but if you attempt to grow it in the wrong climate, then you’ll ultimately be fighting a losing battle.

A plant’s hardiness refers to its ability to survive temperature extremes.

Typically, gardeners use hardiness to refer to the minimum survivable temperatures, but it can also be used to indicate the maximum survivable ones, too.

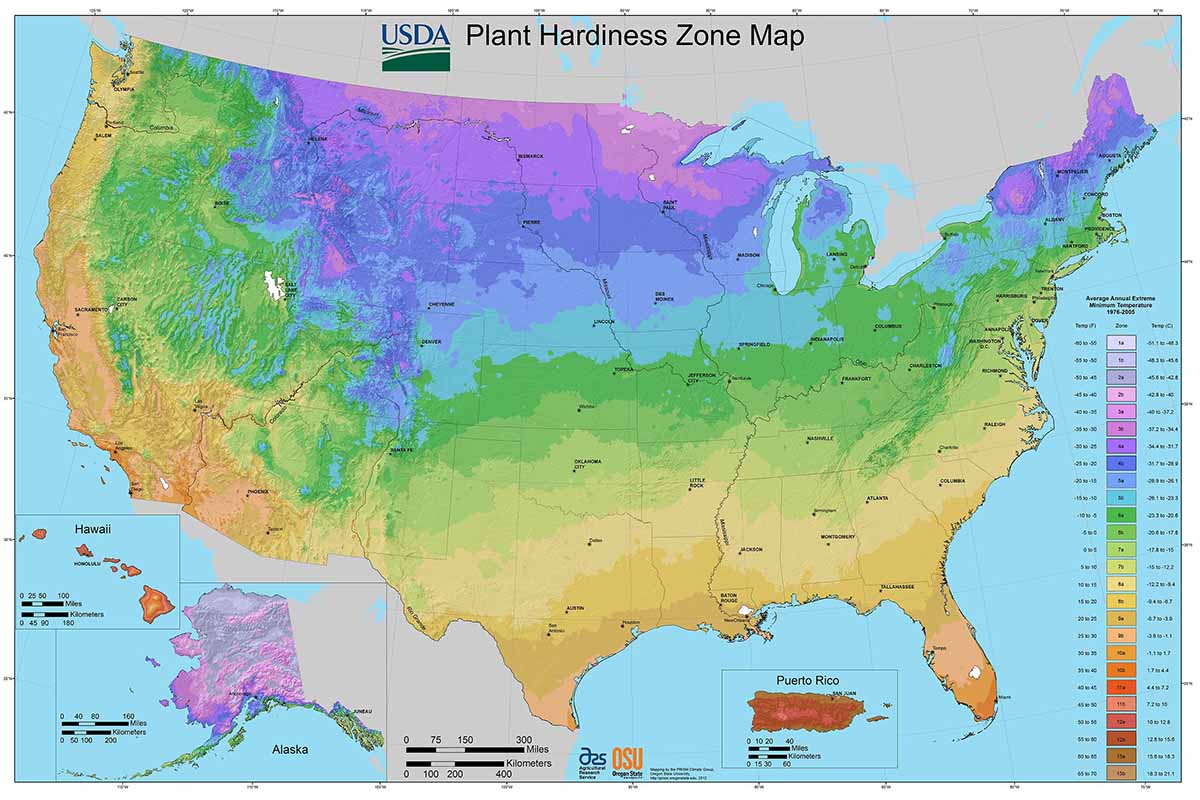

Hardiness zones indicate specific geographical regions with certain average annual minimum temperatures.

Many hardiness zone systems have been developed, but the go-to system in the US is the one that the United States Department of Agriculture came up with. In this system, the higher the zone designation number, the warmer that zone is.

Different species have different hardiness zone ranges, depending on their physiology.

For example, red maple trees are hardy in USDA Zones 3 through 9, while shrimp plants have a hardiness range of USDA Zones 9 to 11. The former is able to survive more cold and temperate climates, while the latter does better in more semi-tropical conditions.

If a plant is grown beyond its hardiness range in either direction, it won’t fare well.

Put it in too hot a climate, and it’ll be fried by summertime. Put it in too cold a climate, and it won’t survive the low temperatures of winter.

It’s important to note however that this actually doesn’t matter too much for annuals, or plants that only live for a single season.

There are also plants that may survive for longer than a single growing season in warm climates, but we’re able to grow them as annuals in cooler locations as well, such as many common summertime vegetables and flowers.

When you buy a plant, it usually comes with a tag that tells you its specific hardiness range. You can also glean this info from seed packets, plant catalogs, high-quality reference books, botanical databases, and gardening websites.

Gardener’s Path is a particularly awesome place to find the hardiness range of a certain species. Type it in the search bar or browse our full collection of growing guides!

Lesson 4: Exposure

Exposure is the amount of sunlight a plant receives, and getting this right is critical for optimizing photosynthesis and health.

Too much light, and the leaves will “scorch,” resulting in a wilted, crispy appearance. Too little light, and the plant won’t be able to make enough food for itself, leaving its growth thin and spindly.

Different exposure requirements outdoors include full sun, partial sun or partial shade, and full shade.

“Full sun” usually means six to eight hours or more of daily sunlight. “Partial sun” and “partial shade” both indicate a need for three to six hours of sunlight per day, while “full shade” means less than three hours of sun a day.

Light doesn’t necessarily have to come from the actual sun, though. Grow lights can be used as a replacement indoors for when sunlight isn’t available.

And indoor light exposure conditions may include bright and direct exposure, bright and indirect light, or indirect light, as well as medium or low-light conditions.

You learn a species’s exposure requirements the same way you would its hardiness, via the tag or conducting a bit of your own research. But studying the plant itself can also tell you a lot about its exposure needs.

Large leaves like the ones a hosta has often indicate a love of shade, since a larger surface area has a greater ability to utilize limited sunlight.

Thin foliage like pine needles tends to do well in full sun – they have such a small surface area that they need all the sun they can catch for adequate photosynthesis. Thick, waxy leaves can take more sun, while thin and delicate ones need more shade.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the southern side of buildings and walls is sunnier and warmer than the northern side, which tends to be shady and cool.

These spots can be used to create microclimates, which are locations that are slightly warmer or cooler than the average temperatures of their hardiness zones.

If you have a species that’s just shy of your garden’s hardiness zone, then a suitable microclimate can really come in handy.

Lesson 5: Soil

Hope you don’t mind getting your hands dirty, because soil will sully those mitts. It’s also what your plants will be growing in, so it’s worth paying attention to.

Believe it or not, soil is alive. It’s a living ecosystem that contains microbes, bugs, fungi, and roots.

Along with these organisms, soil is composed of mineral particles, empty pockets of air, water, and decomposing organic material such as old leaves and rotting animals.

There are three types of mineral particles: sand, silt, and clay, listed in order here from largest to smallest. The proportion of sand, silt, and clay in a soil will determine its texture, which impacts how well it retains water and nutrients.

A soil that’s mostly composed of sand will drain water quickly and fail to hold onto nutrients for long, while a clay-heavy soil can retain more nutrients, but it won’t drain excess water easily.

Silt is an intermediary particle in terms of size, so most gardeners don’t focus on it. And soil with a balance of particle sizes is said to be a loam, which is what you should shoot for in most cases.

Different plants do better in different soils. Many tropicals that hail from beachy areas prefer sandy soils, while a lot of water-loving species actually do well in clay soils. Selecting or planting in the right type of soil from day one makes all the difference.

Just like plants, healthy soils must be cultivated. Regularly amending soils with organic matter such as compost or well-rotted manure will improve their water-holding capacity, fertility, and workability.

Also, it’s important to make sure to avoid compacting soil when possible, as doing so hinders water infiltration, drainage, and root expansion.

A viable alternative to the soil you’d find in the garden is a soilless medium, which uses ingredients such as peat moss and perlite to create a growing medium that’s suitable for container-grown houseplants or greenhouse specimens.

These ingredients are sterile, super easy to adjust and customize, and used to create the perfect combo of drainage, moisture retention, and fertility.

While something like coleus may appreciate being planted in a container filled with a more water-retentive mix, cacti and succulents that hail from more arid environments prefer a sandy soil composition. We’ll touch on the interaction between moisture and soil type a bit more in the next lesson.

Lesson 6: Water

Water is essential. Plants need it for seed germination, propagation, photosynthesis, keeping cellular functions going, staying cool, and remaining upright.

Without it, botanical life – and life on Earth, for that matter – wouldn’t exist.

Since plants take up water through their root systems first and foremost, the roots will need access to H2O. When you water, make sure to irrigate the roots and the surrounding soil.

If you can help it, don’t water the leaves, stems, and branches like they’re the star of a body wash commercial – that’ll just waste water and promote pathogen growth.

Different species have different water requirements. Some need to sit in constant moisture, some prefer their soils to dry out a bit before watering, and others will only need occasional irrigation.

Plants that can grow sans soil such as air plants will require their moisture to be delivered via misting or occasional soaking.

Tags, internet research, and the species’ natural growing sites will all indicate water needs.

But in general, when you do water, you should do so deeply. If the watering is deep, then the roots will be forced to grow longer to take up water as it trickles down the soil profile.

On the other hand, frequent mini-shots of water that get absorbed before moving past the roots won’t incentivize much root growth.

The best time to water is early in the morning, so that plants can start the day off hydrated.

This early morning watering also allows enough time for the specimen and the nearby soil to dry, which prevents any overnight pathogen growth that watering just before dark could cause.

As far as watering frequency goes, it’s important to do so according to the plant’s specific water requirements, as well as its rate of transpiration.

Transpiration rates depend on the environment. High temperatures, strong winds, full sun, and high humidity necessitate more water than cold, windless, cloudy, and dry conditions.

Additionally, sandy soils which drain fast require less water more frequently, while clay soils which retain moisture require more water less frequently.

Age and maturity matters, too. Recently planted specimens in the juvenile stages need more frequent watering than mature, already-established ones.

Lesson 7: Nutrition

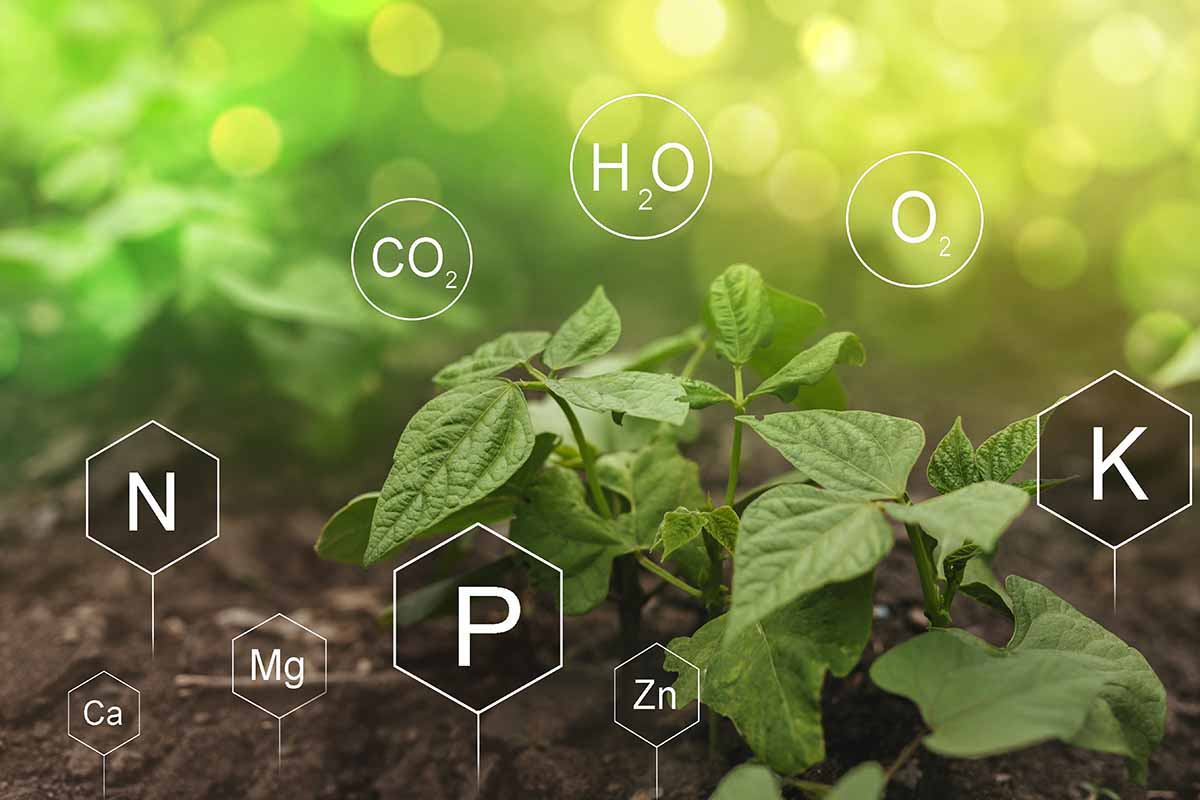

The glucose produced from photosynthesis provides energy to flora, but carbs alone aren’t enough. Other nutrients are also required. Don’t worry… you’ll recognize these from the periodic table.

You’ve got the primary plant macronutrients of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, which are needed in large amounts.

Most commercial fertilizers have a three-number NPK ratio that appears on the label, such as 20-20-20 or 4-3-3. This indicates the ratio of nitrogen to phosphorus and potassium in that fertilizer.

Sulfur, calcium, and magnesium could be considered secondary macronutrients, as they’re also needed in large amounts, but not quite as much as nitrogen, phosphorus, or potassium.

These are usually included as added ingredients in standard fertilizers or sold as separate amendments.

The plant micronutrients boron, chlorine, iron, copper, manganese, molybdenum, and zinc are all necessary, but only in trace amounts.

Provided you choose organic fertilizers over synthetic ones – which is highly recommended for cultivating healthy soil – most of these are naturally provided.

But providing all those nutrients won’t amount to diddly if your soil’s pH is off.

The pH measures how acidic or alkaline your soil is on a logarithmic scale of 0 to 14, with 0 indicating extreme acidity, 7 being neutral, and 14 being extremely basic.

All the aforementioned nutrients fluctuate in availability as you move up and down the spectrum, but soil within a pH range of 5.0 to 7.0 will serve you well for growing many species.

Different species require varying amounts of nutrients and prefer different soil pH values for optimal growth, all of which can be learned from others or researched solo.

The goals of the gardener – such as producing more flowers, more foliage, more fruit, and so on – will also impact one’s fertilization plan, as different nutrients can promote different kinds of growth.

Lesson 8: Maintenance

Many different practices fall under this umbrella, and all of them will leave your specimens better off in the long run.

Pruning is one such practice, and it entails deliberately and manually removing tissues from a plant, whether by hand or via tools such as hand pruners, loppers, and saws. Pruning can be used to achieve many different gardening goals.

Pruning lets you manipulate a specimen’s shape – you can make it more rounded, symmetrical, geometric, or simply eliminate any protruding bits that create a disheveled look.

By removing dead, damaged, and/or diseased tissues, you can eliminate vulnerable spots for pests and pathogens to exploit.

And by removing flower buds or snipping spent flowers in a process known as deadheading, you can actually promote lush leaf growth or even reblooming.

Adding mulch allows you to insulate the root zone, better retain moisture, suppress weed growth, and protect the roots from physical damage.

It adds an additional aesthetic to the garden, and the right choice of mulch can even improve soil nutrition!

Raking up fallen leaves, flower heads, and other tissues will leave your garden looking better, with a lower risk of insect infestations and infections.

Plus, you’ll have some detritus to add to the compost pile!

Lesson 9: Health Care

Being a gardener isn’t all sunshine and roses, although there definitely is some of that involved (especially if you’re growing roses…).

Believe it or not, gardening is a battle. A battle between you and all the pathogens, pests, and physiological conditions that could hurt, disfigure, or even kill your beloved plants.

Step one in keeping your specimens healthy is staying one step ahead of any problems that may arise. Regular examinations will help to prevent any issues from sneaking up on you.

When examining your specimens, check the leaves, flowers, stems, and branches for discoloration, warping, or other forms of damage, as well as symptoms of disease or the presence of pests.

Prevention-wise, there’s a lot you can and should do.

Along with caring for your specimens properly, you should remove nearby plant detritus, use sterile gardening tools, avoid overhead watering, adequately space specimens, and prune away any dead, dying, or diseased tissues.

Avoiding specific pests and diseases common in your area will require specific prevention practices on top of general best practices.

If an infestation or infection occurs, you’ll eventually know, as your plants will be struggling one way or another.

At this point, take a look at the symptoms and try to piece together what might be the culprit. Is it an insect, a disease, or even something physiological or environmental in nature, such as too much moisture?

With enough experience and knowledge, you may be able to make a diagnosis yourself. Otherwise, you’ll have to go to other people and resources for help.

Extension agents, local plantspeople, and your gardening friends are all valuable sources of info, as well as high-quality books, articles, and databases.

And we’re here to help as well! Feel free to reach out in the comments at the end of any related article with your pests and disease questions.

Once you’ve figured out what the problem is, implement the specific recommended control measures. This may not be much of a hassle for minor issues, or it may be a royal pain for others. Either way, don’t let up until the issue is resolved.

But just as superheroes can’t save everybody, you can’t save every plant. Whether you noticed a problem too late or had to deal with a truly severe issue, sometimes your specimens perish. Or at least they may become more trouble to keep alive then they’re worth.

At this point, you should replace the infected specimen with a new one, whether it’s a new species or a resistant form of the original species.

And of course, this enables you to at least learn for next time – a nice segue into the final lesson, actually…

Lesson 10: Never Stop Learning

This is arguably the most important lesson of all in gardening.

Flashback several years to my experience working with the aforementioned knife-throwing lady: at the time, we were both pulling weeds, a near-automatic task that allowed us to talk without doing shoddy work.

On a day of nonstop wedding in the humid heat of Missouri, conversation really helps to keep you sane.

So we’re working and talking, and she’s answering my various questions all the while. And after my bajillionth question was answered, I told her that I was amazed at how she “knew everything about plants.”

And without ceasing her work, she casually said something that permanently changed my outlook:

“No one knows everything about plants, dude.”

No duh, right? But I really needed to hear this spoken to me, especially since I was feeling quite botanically stupid at the time. Horticultural imposter syndrome is real for botany majors, let me tell you… but I digress.

Whether you’re a total neophyte with a black thumb or a lifelong gardener, there’s always something new to learn about plants.

You’ll never know how to identify and care for every species, you won’t understand everything about botany, and there’s always a better gardener out there.

So enjoy the journey of discovery.

Soak up new info like a sponge, whether you seek it out intentionally or pick it up whilst in the gardening trenches. And above all, stay humble – know-it-alls are the worst, no matter the field.

It’s Grow Time!

Congratulations on graduating from our beginners’ course, Growing Plants 101! And kudos to you for discovering a new hobby! Your life will never be the same.

The world of gardening awaits – so what are you waiting for? Go forth and grow!

Have more questions on gardening? Want to share what gardening means to you? The comments section is below.

Want more beginner gardening guides? Check these out next:

Thank you for this!

So much great information!!! Thank you!! I plan (hope) to attempt starting potting some plants with my little kids. It is already June, so I am pretty late… But going to try anyway. Thanks again for the wonderful and easy to understand info!